Structural study of anthrax yields new antibiotic target

Researchers studying anthrax knew they were onto something when they discovered an opponent the bacterium couldn’t outwit. Probing a bit deeper, they discovered this was because the attacker was interacting with something anthrax requires to survive: a carbohydrate in its cell wall. Now, in a study that has implications for the development of a new class of antibiotics, Rockefeller scientists report that they’ve determined the structure of an enzyme involved in the pathway responsible for building this essential carbohydrate.

The research stems from a collaboration between structural biologist C. Erec Stebbins and bacteriologist Vincent Fischetti, and is published online in EMBO reports. The scientists not only describe the crystal structure of an enzyme involved in this vulnerable cell-wall pathway, they were able to use that structure to determine how the enzyme is regulated. And because the mammalian form of this enzyme is slightly different than the anthrax form, the researchers propose that it should be possible to inhibit its activity in bacteria without causing collateral damage to mammalian cells.

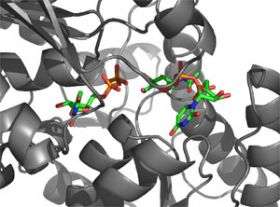

“These enzymes have a unique mode of regulation that’s actually going to tie into the idea of drug development,” says Stebbins, head of the Laboratory of Structural Microbiology. By creating a crystal structure of the enzyme with its substrate attached, he found that the enzyme’s activity is regulated by the very molecules it acts upon.

“So if we could bind a small molecule to the binding site in such a way that it doesn’t productively activate it, we could inhibit the activity of the molecule without inhibiting the same active site of mammalian enzymes,” Stebbins says. This, he hopes, would result in bacteria that are unable to build their cell walls and therefore would be unable to survive.

The anthrax bacterium has two copies of the gene responsible for producing this enzyme. To examine its potential as a drug target, Fischetti — head of the Laboratory of Bacterial Pathogenesis and Immunology — and his lab created a version of the bacterium with one of these genes knocked out. The resulting mutants grew much, much more slowly, Stebbins says, which tells them that if they could come up with an inhibitor, “it would probably hit these things hard.”

Also promising is that the same inhibitor site exists in a number of related bacteria, including those that cause staphylococcal infections and pneumonia. So if researchers could devise a drug that targets this site, it might be versatile enough to act against a range of bacteria. “It’s still in the very early stages,” Stebbins says, “but the structure gave us a very interesting idea for how we might tailor our drug search.”

Link:

Source: Rockefeller University