Nature's quality control in yeast

(�鶹��ԺOrg.com) -- Scientists know that in yeast cells, as in other cells, it’s the job of ribosomes to make proteins out of amino acids using information coded in the messenger RNA (mRNA).

But what hasn’t been well understood thus far is how this process works. Now Rutgers researchers Xinfu Jiao and Megerditch Kiledjian have discovered that a protein called Rai1 has what amounts to a natural quality-control mechanism that makes sure the process gets started on the right track. Their discovery is important to scientists because, until now, scientists thought that mRNA attached to the ribosomes without a hitch. Kiledjian and Jiao have discovered that there are hitches, and that those hitches get fixed naturally. Also, now that the process is better understood, that understanding could help researchers manipulate the system.

Jiao, a research associate, and Kiledjian, a professor of cell biology and neuroscience in Rutgers’ School of Arts and Sciences, have published their results in the journal Nature.

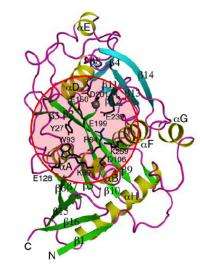

The researchers’ discovery has to do with the changes RNA undergoes on its way to the ribosomes. RNA is transcribed from DNA, and carries all the information the ribosomes need to make proteins. But the RNA goes through a maturation process in which it’s acted on by enzymes, including Rai1, and is eventually able to deliver its information to the cells’ ribosomes.

Scientists refer to RNA as precursor mRNA, or just pre-mRNA, when RNA is in its transitional state of molecular adolescence. On its way to the ribosomes, pre-mRNA undergoes a series of modifications, one of which is called “capping.” A “cap” molecule is attached to the pre-mRNA’s front end to protect it from decaying before it can do its work. The ribosomes also need the cap in order to recognize the incoming mRNA.

Kiledjian and Jiao write that scientists have always assumed that capping happened automatically, or at least routinely, as the RNA matured and delivered its information to the ribosomes.

Not so, as it turns out. Kiledjian and Jiao suggest that the process of capping pre-mRNA doesn’t always occur seamlessly. When nutrients such as glucose or amino acids are removed from the environment, the developing yeast cell makes mRNAs that have an “aberrant caps.”

Jiao and Kiledjian report that yeast, in nature and in the lab, contains an enzyme that “de-caps” the pre-mRNA at the beginning of its transition if there’s something amiss with the cap. This means cells have a built-in instrument that checks their work as they manufacture proteins.

It’s a long way from yeast cells to human cells, but Kiledjian thinks he and Jiao have given cell biologists who work on human cells something to think about. “Any time aberrant molecules, RNA or otherwise, accumulate in a cell, it increases the likelihood that normal cellular processes could be disrupted and could potentially lead to a disease state if left unchecked,” he said. “I’m guessing defects in Dom3Z, the mammalian homolog of Rai1, will eventually be found to contribute to at least some forms of human disorders.”

Provided by Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey