Real-world programming in the classroom

In undergraduate computer-science classes, homework assignments are usually to write programs, and students are graded on whether the programs do what they're supposed to. Harried professors and teaching assistants can look over the students' code and flag a few common and obvious errors, but they rarely have the time coach the students on writing clear and concise code.

In the real world, however, code clarity is as important as software performance. Large software projects can involve hundreds of programmers, each working on a small corner of an application, and over the course of a project, personnel turnover can be high. Testing, revising and updating software may require people to review code that they had no hand in writing. If the code isn’t intelligible, engineers can waste a huge amount of time just figuring out how an existing program does what it does.

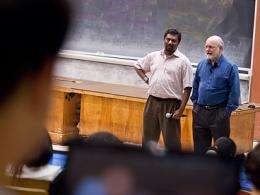

Professors of computer science Charles E. Leiserson and Saman Amarasinghe, who co-teach a class called Performance Engineering of Software Systems, believe that undergraduates should be taught to write clear code, not just running code. So this fall, for the second year in a row, students in the class won’t just have their projects graded by their teaching assistants; they’ll also have their code reviewed by senior programmers from the Boston area, who volunteer their time through a program that Amarasinghe and Leiserson call Masters in the Practice of Software Systems Engineering, or MITPOSSE.

The roughly 70 students in the class work on four major projects a semester, in two-person teams. After each project is submitted, students from separate teams are paired, and each pair meets with one of the professional programmers for a code review. The code review lasts between 60 and 90 minutes, and each of the 20-odd professionals meets with two pairs of students. The code reviews don’t count toward the students’ final grades, but they are mandatory.

The mother of invention

Leiserson and Amarasinghe introduced the class, which they teach only in the fall, three years ago. The first year, enrollment was lower than it is now, and the professors decided to hold their own half-hour code reviews with individual students after each project. “That killed us,” Leiserson says. “Even though we had a small class at the time, it was clearly not scalable.” So in the summer of 2009, Amarasinghe and Leiserson put the word out among friends and colleagues, former students, and members of the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory’s Industry Affiliates Program that they were recruiting seasoned programmers to serve as mentors to their students in the fall. “We got a tremendous response,” Leiserson says. Indeed, in both 2009 and 2010, the professors had to turn away applicants to the program. To Amarasinghe and Leiserson’s knowledge, theirs is the first computer science class in the country to incorporate code review with professional software engineers.

According to Amarasinghe, the chief purpose of the MITPOSSE program is to help students develop their own programming styles. By “style” he means things like selecting names for variables, so that it’s clear to later readers what they refer to; avoiding the use of so-called “magic numbers,” numerals that are simply inserted into equations without explanation (the better practice, Amarasinghe explains, is to assign the number a name that indicates its purpose, and then use the name in subsequent equations); indenting lines of code; and, most important, adding comments — lines of text that appear next to the program code and explain what it’s doing, but which the computer ignores when converting code into an executable program.

In many computer-science classes, Amarasinghe says, professors trying to preserve intelligibility will insist on a particular style of coding, which may not be natural for some students and, he says, can actually lead to bad code. “The way we look at programming, it’s like writing an English paper,” he says. “If you are in English class, there’s no set way of writing.” What’s important is that a programmer’s style be consistent, not that it slavishly ape some model.

Less is more

Of course, all computer-science professors emphasize the importance of good comments, but busy students usually try to get their programs working and then stick in comments in whatever time they have left. Reid Kleckner, who took Amarasinghe and Leiserson’s class as an undergraduate last year and, as a master’s candidate, is a teaching assistant this year, says that the MITPOSSE reviews can help some students get a better grasp of the purpose of comments. “Usually, students hear, ‘Comment your code,’ and they say okay, line by line, ‘This is what this line does, this is what this line does.’” But, Kleckner explains, comments are in fact more useful when they are spare and descriptive. A program might, for instance, include some clever but obscure procedure that makes it run more efficiently. Simply commenting in the margin that, say, the procedure rounds a number up to the nearest power of two may be all the information the reader needs. “You don’t need to say, here are the arithmetic operations that I am performing, and they achieve this result. Here’s my mathematical proof,” Kleckner says.

Moreover, Kleckner says, with the MITPOSSE approach, “It’s not just graduate students telling you how to write code. It’s coming from a figure of authority, in some sense.” He laughs and adds, “Not that the T.A. is not a figure authority.” But a T.A. is not a prospective employer.

Indeed, for the mentors, some of the appeal of volunteering for the program may very well be the opportunity to scout talent. So Leiserson and Amarasinghe have drawn up a set of rules that the mentors agree to abide by, including “no recruiting, hints at job opportunities, offers of summer internships, lab tours, free dinners, etc.,” until “the semester is over and no power relationship exists.”

But many of the mentors simply find the work intrinsically satisfying. Barry Perlman, who as an independent software consultant doesn’t have any job vacancies to fill, volunteered with the program last year and came back again this year. “I felt like I was doing something useful,” he says. “The world doesn’t need more software engineers; the world needs better software engineers.” Andrew Lamb, too, has joined the MITPOSSE for a second year in a row. He works for a small software company, and though he acknowledges that “it’s nice to get that name out there,” the company isn’t currently looking for any new hires. But, Lamb says, “when they have some question and I’m able to answer it, and their eyes light up, and they say, ‘I get it, I get it,’ that’s very cool.”

This story is republished courtesy of MIT News (), a popular site that covers news about MIT research, innovation and teaching.

Provided by Massachusetts Institute of Technology