Scientists hope for data after historic but dodgy comet landing

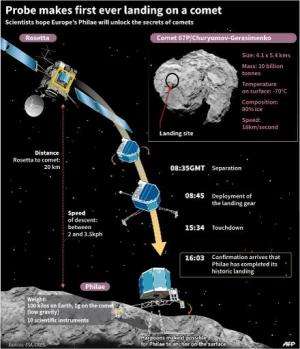

European scientists were hoping for a stream of data Thursday after a robot lab made the first-ever landing on a comet, a key step in a marathon mission to probe the mysteries of space.

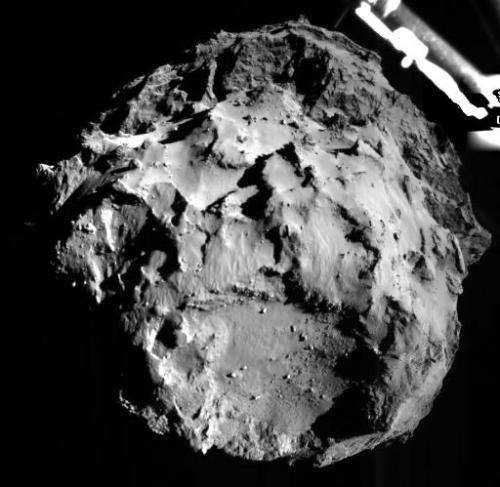

Operation chiefs in Darmstadt, Germany, on Wednesday said the lander Philae failed to anchor to comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on landing, but still managed to send back scientific information.

The 100-kilogramme (220-pound) explorer may have plopped down in a soft, sand-like material or may be lightly touching the surface, they speculated.

More would be known on Thursday when Philae makes scheduled contact with its mothership, Rosetta, landing manager Stephan Ulamec said.

"Hopefully, we are sitting there on the surface at a position different to the original landing and can continue our science," Ulamec said.

The agency was to brief the press at 1300 GMT.

The European Space Agency (ESA) is ecstatic at the operation and NASA—the world's most successful space agency and an expert at difficult landings—itself heaped praise on the exploit.

Equipped with 10 instruments, Philae was designed to carry out the first-ever scientific experiments on a comet, providing the jewel in a crown of a massively complicated project more than two decades in the making.

Getting from Earth to a comet that is travelling towards the Sun at 18 kilometres per second (11 miles per second) was a landmark in space engineering and celestial mathematics.

The 1.3-billion-euro ($1.6-billion) Rosetta mission was approved in 1993.

Rosetta, carrying Philae, was hoisted into space in 2004, and took more than a decade to reach its target in August this year, having used the gravitational pull of Earth and Mars as slingshots to build up speed.

The pair covered 6.5 billion kilometres together before Wednesday's separation prior to landing.

Seen by the superstitious as harbingers of good or evil, comets are viewed by astrophysicists as time capsules of the nascent Solar System.

They comprise ancient ice and dust, the rubble of the material that went into the making of the planets 4.6 billion years ago.

According to one hypothesis, they may have given Earth the gift of life by pounding it with ice that made the oceans and carbon molecules that provided the building blocks of organisms.

Philae was designed to come into land at a gentle 3.5 kilometres per hour, then fire two harpoons into a surface that engineers hoped would provide sufficient grip while the robot conducts experiments with 11 scientific instruments.

However there were indications that these landing harpoons had failed to deploy, ground control said.

Envisaged tests include drilling through the comet surface and analysing the samples for chemical signatures.

Science goals

In Toulouse, France, astrophysicist Philippe Gaudon, who heads the Rosetta mission at French space agency CNES, said it would be difficult for Philae to drill if it was not secured.

"However, Philae has not tipped over and seems to be stabilising," Gaudon said.

"And a certain number of instruments are continuing to operate, mainly for measuring temperature, vibration, magnetism and so on."

Philae is designed to operate for about 60 hours on a stored battery charge, but several months more if it can get replenishment from sunlight.

The 100-kilo (220-pound) lander complements 11 instruments aboard Rosetta, a three-tonne orbiter that is doing four-fifths of the expected scientific programme from orbit.

Whatever happens to Philae, Rosetta will continue to escort the comet as it loops around the Sun.

On August 13, 2015, "67P" will come within 186 million kilometres of the star.

The mission is scheduled to end in December 2015, when the comet heads out of the inner Solar System.

At this point, Rosetta will once again come close to Earth's orbit, more than 4,000 days after launch.

Rosetta and Philae: 10 figures

Ten facts to sum up orbiter Rosetta and robot lab Philae, Europe's comet-chasing duo:

- 10 years and eight months: How long Rosetta and its payload Philae spent together after their launch on March 2, 2004.

- 6.5 billion kilometres (four billion miles): The distance they travelled together before Philae ejected and headed towards 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on Wednesday.

- 510 million kilometres (320 million miles): Current distance of comet from Earth.

- 18 kilometres per second (11 miles per second): The speed at which the comet and its orbiter are zipping towards the Sun.

- 3.5 km per hour (2.2 miles per hour): The pace of Philae's expected landing.

22.5 km (14 miles): The approximate height at which Rosetta released Philae.

- Seven: Roughly the number of days that Philae can work without its batteries getting a solar recharge.

- 28 minutes and 20 seconds: The time it will take signals from Rosetta to reach Earth.

- 1.3 billion euros ($1.6 billion): The total cost of the mission—equivalent to the price of about four Airbus A380 jetliners.

- 10: The number of science instruments onboard Philae, adding to 11 on Rosetta.

Rosetta mission: A timeline

Timeline of Europe's Rosetta mission, which on Wednesday sent down a lander to probe a comet in deep space:

- March 2, 2004: Liftoff from the European Space Agency's launchpad in Kourou, French Guiana by an Ariane 5 rocket.

- March 2005: Rosetta encounters the Earth, using planet's gravity as a slingshot to boost speed.

- February 2007: Flies around Mars at a distance of just over 200 kilometres (120 miles) for a second gravitational assist.

- November 2007: Second Earth flyby.

- September 2008: Rosetta flies by asteroid 2867 Steins at a distance of around 800 kms.

- November 2009: Third Earth flyby. Rosetta now at top speed as it flies through the asteroid belt. Gets a close observation of the space rock 21 Lutetia (July 2010).

- June 2011-January 20, 2014: At maximum distance (800 million kms) from the Sun and a billion kms from home, Rosetta goes into hibernation to conserve energy.

- January-May 2014: Rosetta gets wakeup call, fires thrusters to gradually brake its speed.

- August 6, 2014: Rosetta arrives at Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Has 11 onboard cameras, radar, microwave, infrared and other sensors to analyse its surface and gases escaping from its head.

- November 12, 2014: Rosetta sends down a 100-kilogramme (220-pound) robot laboratory, Philae.

Looking ahead

- 2015: "67P" loops around the Sun, approaching on August 13 to within 186 million kms (116 million miles) of the star.

- December 2015: Scheduled end of mission. Escorted by Rosetta and with Philae on its back, the comet heads out of the inner Solar System. At this point, Rosetta will once again come close to Earth's orbit, more than 4,000 days after launch.

Mission Rosetta: Behind the names

What those names mean in Europe's comet-chasing Rosetta mission:

- ROSETTA: Named after the Rosetta Stone, now housed in the British Museum, which helped unravel one of the greatest puzzles of the early 19th century. Bearing a carved text in hieroglyphs and Greek, the stone was found by French soldiers in 1799 near the village of Rashid (Rosetta) in the Nile delta. An English physicist, Thomas Young, and a French scholar, Jean-Francois Champollion, were able to figure out most of the hieroglyphs thanks to the Greek equivalent. The mysterious culture of the Pharaohs was at last explained.

- PHILAE: A 15-year-old Italian girl, Serena Olga Vismara, proposed Philae in a competition to name Rosetta's scientific payload, a 100-kilogramme (220-pound) lander. The name comes from an obelisk found on the island of Philae on the Nile. Now standing in a garden of a country house in the southern English county of Dorset, the obelisk has a bilingual inscription bearing the names of Cleopatra and Ptolemy. It gave Champollion the clinching clue to the hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone.

- AGILKIA: The designated landing site for Philae. Named after an island on the Nile which became the new home of Pharaonic temples transferred from Philae when the Aswan Dam threatened to flood the complex.

- 67P/CHURYUMOV-GERASIMENKO: Named after two Soviet-era Ukrainian astronomers credited with discovering it in 1969—Klim Churyumov of the University of Kiev and Svetlana Gerasimenko of the Institute of Astrophysics in Dushanbe, Tajikistan. "P" refers to a periodic comet, or a comet whose revolution around the Sun is less than 200 years, while "67" refers to its number on a list.

© 2014 AFP