Regulating the use of genetic sequence data

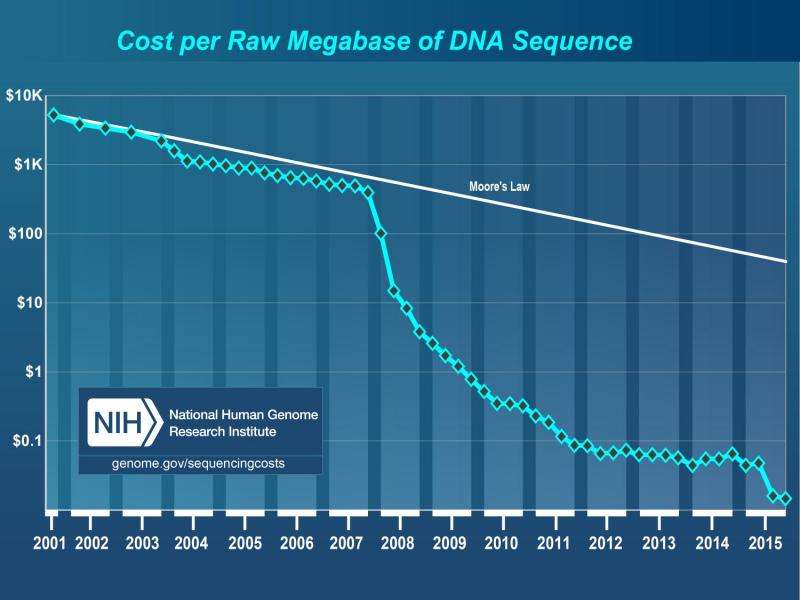

Last month, researchers from the Universität Marburg reported mixing 12 enzymes from three spheres of life, including plants, humans and microbes, to create an that is more efficient at fixing CO2 than plants. This achievement is just the latest in a host of projects to generate improved metabolic pathways for catalysis or entirely new ones, ranging from artificial to . Such work is made possible by the falling cost of and synthesis, which means it is possible to 'read-and-write' the DNA required to make a variety of enzymes for less than $1000.

Genetic sequence data and the Nagoya Protocol

These projects utilize the diversity of enzymes in nature to select the best catalyst for a job. This has raised concerns about the political grounds of bioprospecting and biopiracy (the latter being bioprospecting that exploits plant and animal species by claiming patents that restrict their general use), and resulted in questions about how should be regulated in the same way as or in relation to other 'genetic resources' (such as seeds).

These concerns arise out of a long history of exploitation. , wealthy families, or private donors, have collected samples around the globe, often with the help of indigenous peoples, without returning any benefits. Entire sciences, scientific careers, and industries have been made and are made thanks to these collecting campaigns. Despite its importance, it is surprising that collecting only became the subject of international governance agreements in recent decades. Currently, use of genetic resources is regulated by the (NP) which sets out the conditions under which they can be transferred from one country to another.

'[These agreements] are potentially win-win' says , an expert on regulatory affairs, 'providing access to genetic diversity, and allowing benefits that come from discoveries to be shared.'

This topic is currently under discussion at the of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) (COP13). It is argued that, if sequence information is not covered by the Nagoya protocol, it could , opening a new round of exploitation. A representative of Namibia explained 'The widespread and woeful denial of benefit-sharing is undermining NP [Nagoya Protocol]' and as a prime they example pointed to 'the spurious argument that use of digital genetic sequences isn't 'access' so there are no benefit sharing obligations.' They went on to state: 'Let's be perfectly clear – such resources are only valuable because of the information they encode'.

Concerns about regulating sequence information

However, others have also the protocol, particularly as regards to the regulatory burden, with suggestions that it could act as a disincentive to research and development, or causing problems when there needs to be rapid sharing of information, such as . Exchanges of material must be authenticated by obtaining an 'Internationally Recognized Certificate of Compliance (IRCC)', a process that is currently time consuming and costly: the . There also remains a question over what period of time the protocol applies to – if it covers material collected after it came into force () or anything following the start of the Convention for Biological Diversity (). Sometimes when people highlight such practical difficulties, it is because they want to depoliticize access and benefit sharing, turning it into a 'purely technical' matter. It is a persistent irony that the latter is one of the most deeply political arguments it is possible to make.

What might regulation of sequence information mean in practice?

Bruce suggests if one is to understand what is likely to happen if sequence information is regulated, it is best to look at what is (For examples of potential answers to 'problem situations' including those raised refer to the correspondent text box on the left).

Non-compliance could result in patent invalidation or criminal prosecution. There have already been a number of high-profile lawsuits around the use of biological material: for a genetically modified variety of eggplant, against various companies developing the and against Nestlé in South Africa , a plant native to the country.

Your responses

, and surround the regulation of digital sequence information, and there are many different views and ideas. Nor do the issues of DNA sequencing and synthesis begin and end with the Nagoya protocol. A full understanding would require considerably more attention to the Convention on Biological Diversity.

Nevertheless, here is an opportunity to join a conversation about what kind of science and industry you want to see in the world, to show different perspectives, rather than assuming or demanding that the way you see things is obviously the 'fairest' or 'most sensible'. By and large, the people involved with the regular use of biological resources tend to have very complex views regarding what should/should not be subject to ABS agreements, and for what reasons. We look forward to hearing from you.

Provided by Public Library of Science

This story is republished courtesy of PLOS Blogs: .