The three-minute story of 800,000 years of climate change with a sting in the tail

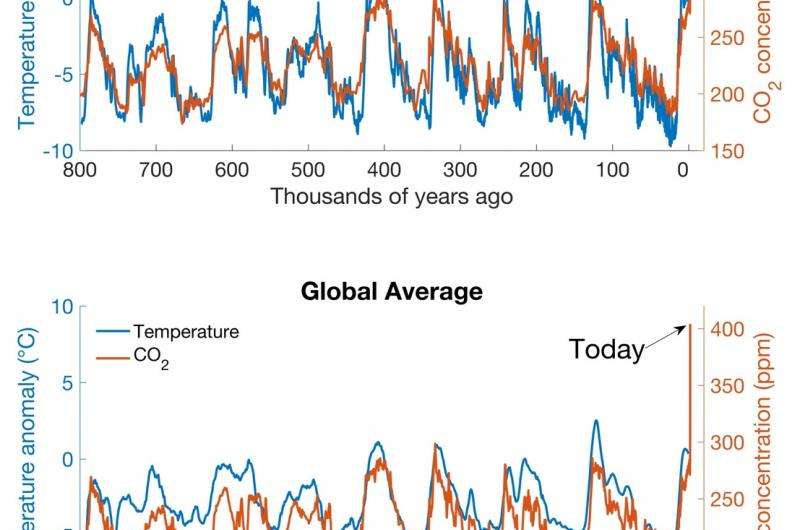

There are those who say the climate has always changed, and that carbon dioxide levels have always fluctuated. That's true. But it's also true that since the industrial revolution, COâ‚‚ levels in the atmosphere have climbed to levels that are unprecedented over hundreds of millennia.

So here's a short video we made, to put recent climate change and carbon dioxide emissions into the context of the past 800,000 years.

The temperature-COâ‚‚ connection

Earth has a , and it is really important. Without it, the average temperature on the surface of the planet would be about -18℃ and human life would not exist. Carbon dioxide (CO₂) is one of the gases in our atmosphere that traps heat and makes the planet habitable.

We have known about the greenhouse effect for well over a century. About 150 years ago, a physicist called used laboratory experiments to demonstrate the greenhouse properties of COâ‚‚ gas. Then, in the late 1800s, the Swedish chemist first calculated the greenhouse effect of COâ‚‚ in our atmosphere and linked it to past ice ages on our planet.

Modern scientists and engineers have explored these links in intricate detail in recent decades, by drilling into the ice sheets that cover Antarctica and Greenland. Thousands of years of snow have compressed into thick slabs of ice. The resulting ice cores can be more than 3km long and extend back a staggering 800,000 years.

Scientists use the chemistry of the water molecules in the ice layers to see how the . These ice layers also trap tiny bubbles from the ancient atmosphere, allowing us to .

Temperature and COâ‚‚

The ice cores reveal an through the ice age cycles, thus proving the concepts put forward by Arrhenius more than a century ago.

In previous warm periods, it was not a COâ‚‚ spike that kickstarted the warming, but in Earth's . COâ‚‚ played a big role as a natural amplifier of the small climate shifts initiated by these wobbles. As the planet began to cool, more COâ‚‚ dissolved into the oceans, reducing the greenhouse effect and causing more cooling. Similarly, COâ‚‚ was released from the oceans to the atmosphere when the planet warmed, driving further warming.

But things are very different this time around. Humans are responsible for adding huge quantities of extra CO₂ to the atmosphere – and fast.

The speed at which COâ‚‚ is rising has no comparison in the recorded past. The fastest natural shifts out of ice ages saw COâ‚‚ levels increase by around . It might be hard to believe, but humans have emitted the equivalent amount in .

Before the industrial revolution, the natural level of atmospheric COâ‚‚ during warm interglacials was around 280 ppm. The frigid ice ages, which caused kilometre-thick ice sheets to build up over much of North America and Eurasia, had COâ‚‚ levels of around 180 ppm.

Burning fossil fuels, such as coal, oil and gas, takes ancient carbon that was locked within the Earth and puts it into the atmosphere as COâ‚‚. Since the industrial revolution humans have burned an enormous amount of fossil fuel, causing atmospheric COâ‚‚ and other greenhouse gases to skyrocket.

In mid-2017, atmospheric COâ‚‚ now stands at . This is completely unprecedented in the past 800,000 years.

The is . The that by the end of this century we will get to more than 4℃ above pre-industrial levels (1850-99) if we continue on a high-emissions pathway.

If we work towards the goals of the Paris Agreement, by rapidly curbing our COâ‚‚ emissions and developing new technologies to remove excess COâ‚‚ from the atmosphere, then we stand a chance of .

The fundamental science is very well understood. The evidence that climate change is happening is abundant and clear. The difficult part is: what do we do next? More than ever, we need strong, cooperative and accountable leadership from politicians of all nations. Only then will we avoid the worst of climate change and adapt to the impacts we can't halt.

Provided by The Conversation

This article was originally published on . Read the .![]()