A single photon reveals quantum entanglement of 16 million atoms

Quantum theory predicts that a vast number of atoms can be entangled and intertwined by a very strong quantum relationship, even in a macroscopic structure. Until now, however, experimental evidence has been mostly lacking, although recent advances have shown the entanglement of 2,900 atoms. Scientists at the University of Geneva (UNIGE), Switzerland, recently reengineered their data processing, demonstrating that 16 million atoms were entangled in a one-centimetre crystal. They have published their results in Nature Communications.

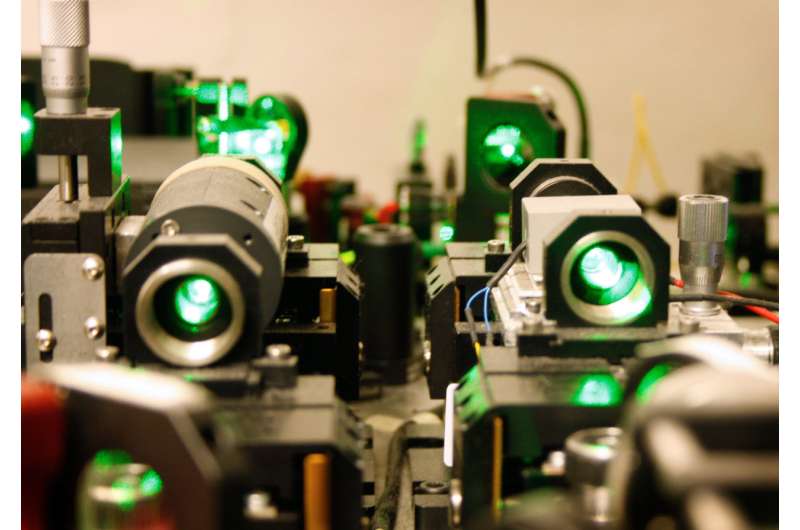

The laws of quantum physics allow immediately detecting when emitted signals are intercepted by a third party. This property is crucial for data protection, especially in the encryption industry, which can now guarantee that customers will be aware of any interception of their messages. These signals also need to be able to travel long distances using special relay devices known as quantum repeaters—crystals enriched with rare earth atoms and cooled to 270 degrees below zero (barely three degrees above absolute zero), whose atoms are entangled and unified by a very strong quantum relationship. When a photon penetrates this small crystal block, entanglement is created between the billions of atoms it traverses. This is explicitly predicted by the theory, and it is exactly what happens as the crystal re-emits a single photon without reading the information it has received.

It is relatively easy to entangle two particles: Splitting a photon, for example, generates two entangled photons that have identical properties and behaviours. Florian Fröwis, a researcher in the applied physics group in UNIGE's science faculty, says, "But it's impossible to directly observe the process of entanglement between several million atoms since the mass of data you need to collect and analyse is so huge."

As a result, Fröwis and his colleagues chose a more indirect route, pondering what measurements could be undertaken and which would be the most suitable ones. They examined the characteristics of light re-emitted by the crystal, as well as analysing its statistical properties and the probabilities following two major avenues—that the light is re-emitted in a single direction rather than radiating uniformly from the crystal, and that it is made up of a single photon. In this way, the researchers succeeded in showing the entanglement of 16 million atoms when previous observations had a ceiling of a few thousand. In a parallel work, scientists at University of Calgary, Canada, demonstrated entanglement between many large groups of atoms. "We haven't altered the laws of physics," says Mikael Afzelius, a member of Professor Nicolas Gisin's applied physics group. "What has changed is how we handle the flow of data."

Particle entanglement is a prerequisite for the quantum revolution that is on the horizon, which will also affect the volumes of data circulating on future networks, together with the power and operating mode of quantum computers. Everything, in fact, depends on the relationship between two particles at the quantum level—a relationship that is much stronger than the simple correlations proposed by the laws of traditional physics.

Although the concept of entanglement can be hard to grasp, it can be illustrated using a pair of socks. Imagine a physicist who always wears two socks of different colours. When you spot a red sock on his right ankle, you also immediately learn that the left sock is not red. There is a correlation, in other words, between the two socks. In quantum physics, an infinitely stronger and more mysterious correlation emerges—entanglement.

Now, imagine there are two physicists in their own laboratories, with a great distance separating the two. Each scientist has a a photon. If these two photons are in an entangled state, the physicists will see non-local quantum correlations, which conventional physics is unable to explain. They will find that the polarisation of the photons is always opposite (as with the socks in the above example), and that the photon has no intrinsic polarisation. The polarisation measured for each photon is, therefore, entirely random and fundamentally indeterminate before being measured. This is an unsystematic phenomenon that occurs simultaneously in two locations that are far apart—and this is exactly the mystery of quantum correlations.

Journal information: Nature Communications

Provided by University of Geneva