Fossil fuel subsidies need to go – but what about the poorer people who rely on cheap energy?

Almost all governments in the world joined the Paris agreement in 2015 in an effort to tackle climate change. In the same year, many of the same governments paid about in direct and indirect subsidies to help people buy fossil fuels.

Subsidies are government policies which make energy cheaper than under normal market conditions. They mostly go towards fossil fuels, since most of the energy we use comes from oil, gas or coal. As one of us noted in a review published in the journal , fossil fuel subsidies are a popular and pervasive tool for helping people across the world have access to energy.

But it isn't clear whether both trends are possible. Isn't there a contradiction between subsidising fossil fuels and meeting Paris climate targets? And, if the subsidies are removed, won't many people suffer without cheap energy?

Though recent analysis shows that the worldwide removal would not , there are beyond reducing emissions.

Subsidies are inefficient

There is increasing disillusionment with subsidies. As one senior OECD official : "Subsidies often introduce economic, environmental, and social distortions with unintended consequences. They are expensive for governments and may not achieve their objectives while also inducing harmful environmental and social outcomes."

Therefore, there is growing political momentum against fossil fuel subsidies. In 2016, the G20 leaders reaffirmed an earlier pledge to phase them out.

In theory, reforming or even completely removing these subsidies should not be a particularly difficult task because there is increasing evidence that they are not especially effective at poverty alleviation: the very reason they were introduced in the first place.

For example, documented that across 20 developing countries the poorest fifth of the population received on average just 7% of the overall subsidy benefit, whereas the richest fifth received almost 43%. Another study and found that, of the US$22.5 billion spent on fossil fuel subsidies in 2010, less than US$2 billion benefited the poorest 20%. This is essentially because poorer households in poor countries use less fuel than wealthier households, even when energy is subsidised.

Subsidies can also paradoxically lead to energy shortages. In , fixed prices for electricity, diesel and petrol have resulted in shortages when those prices fall below international market levels. This has convinced suppliers to focus on exports to China and Thailand rather than domestic use, and has stripped them of the revenues needed for infrastructure.

Why does such an obviously inefficient policy stay around? One easy explanation may be that the main obstacle to subsidy reform is the fossil fuel lobbies. But recent research shows that the situation is not so simple.

Subsidies still help the poor

Most subsidies were introduced to serve a social mission and some have done it really well. Examples include the US's or the UK's , which helped 2.3m "fuel poor" homes.

In developing countries, subsidies are also typically introduced as well-meaning policies to support lower income groups and thus gain support from large numbers of people. And, although they are an extremely inefficient policy to support development, subsidies are sometimes the best option when .

Around the world, are aimed at consumers rather than producers. It's true that the bulk of this money goes to richer households, but since energy makes up a larger share of poorer household budgets, subsidies are relatively for people on low incomes. Many governments therefore fear that removing them risks political upheaval.

A political opportunity

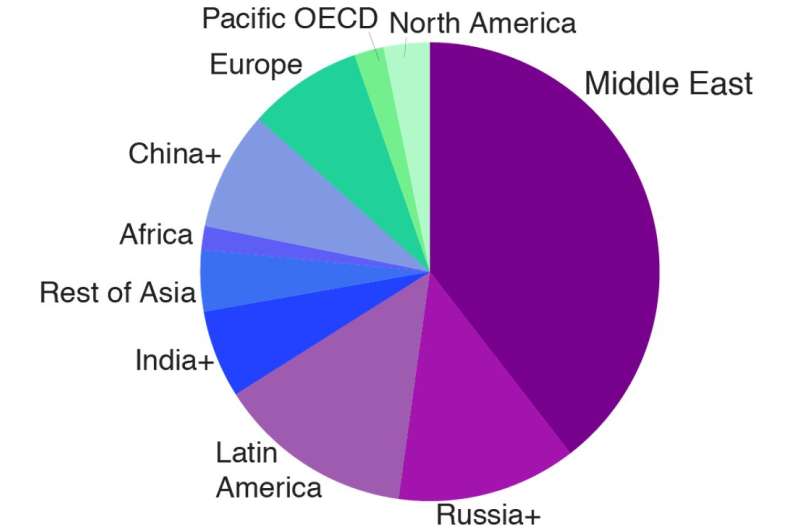

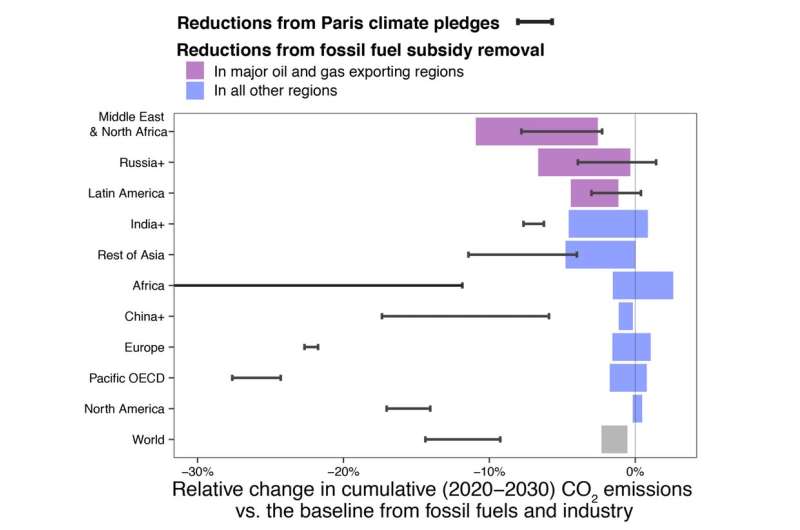

Despite this difficulty, the tension between providing energy subsidies to the poor and protecting the climate is not as insurmountable as it may seem. A led by one of us shows that, if fossil fuel subsidies were removed worldwide, the largest emissions reductions would occur in oil and gas exporting regions: Russia and some of its neighbours, the Middle East, North Africa and Latin America.

Most subsidies originate in these regions, but they also benefit fewer people living below the poverty line than in lower income countries such as India. This presents a unique political opportunity, because it is these oil and gas exporting countries where subsidy cuts would be most welcomed, as government budgets are squeezed by low oil prices.

The trick to , even in the face of an oil price rise, is to combine them with effective pro-poor policies. Examples include India paying for cooking gas for those households , or the way Indonesia and Iran have reallocated energy subsidy money to help finance and respectively.

Ultimately, subsidy reform is not impossible, but neither is it easy. To gain maximum benefits for the climate while doing the minimum harm to the poor, reforms must be carefully targeted at the regions and sectors where they will be most effective.

Journal information: Nature

Provided by The Conversation

This article was originally published on . Read the .![]()