What are rare earth elements? Four questions answered

Most Americans use rare earth elements every day – without knowing it, or knowing anything about what they do. That could change, as these unusual materials are becoming a between the U.S. and China.

, a geologist whose specialty is X-ray analysis of rocks and minerals to determine their chemical composition, and who teaches mineralogy at Franklin and Marshall College, explains more about these little-known and fascinating elements – and the modern electronics they make possible.

1. What are rare earth elements?

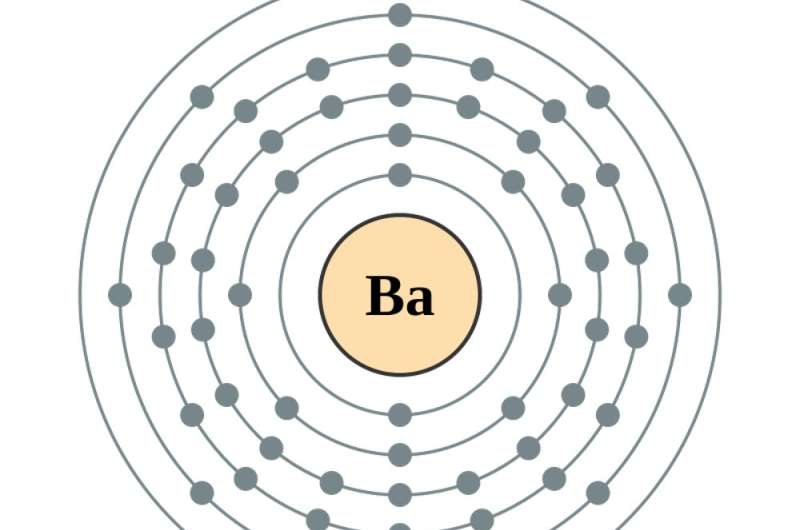

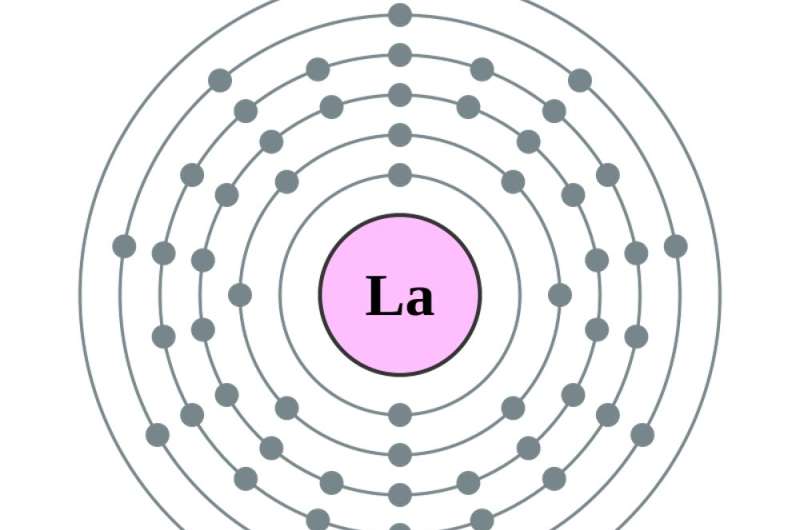

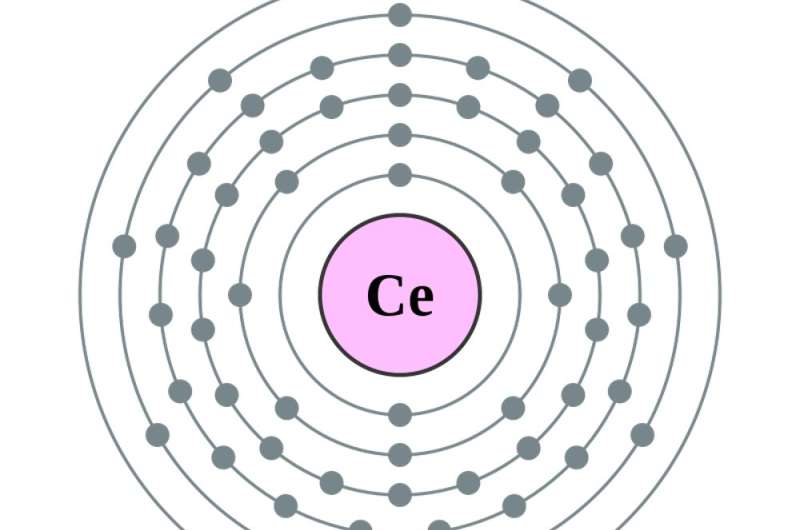

Strictly speaking, they are elements like others on the periodic table – such as carbon, hydrogen and oxygen – with atomic numbers 57 to 71. There are that are sometimes grouped with them, but the main rare earth elements are those 15. To make the first one, lanthanum, start with a barium atom and add one proton and one electron. Each successive rare earth element adds one more proton and one more electron.

It's significant that there are 15 rare earth elements: Chemistry students may recall that when electrons are added to an atom, they , called orbitals, which are like concentric circles of a target around the bull's-eye of the nucleus.

The innermost target circle of any atom can contain two electrons; adding a third electron means adding one in the second target circle. That's where the next seven electrons go, too – after which electrons must go to the third target circle, which can hold 18. The next 18 electrons go into the fourth target circle.

Then things start to get a bit odd. Though there is still room for electrons in the fourth target circle, the next eight electrons go into the fifth target circle. And despite more room in the fifth, the next two electrons after that go into the sixth target circle.

That's when the atom becomes barium, atomic number 56, and those empty spaces in earlier target circles start to fill. Adding one more electron – to make , the first in the series of rare earth elements – puts that electron . Adding another, to make cerium, atomic number 58, adds an electron to the fourth circle. Making the next element, praseodymium, actually moves the newest electron in the fifth circle to the fourth, and adds one more. From there, .

In all elements, the electrons in the outermost circle largely influence the element's chemical properties. Because the rare earths have identical outermost electron configurations, their .

2. Are rare earth elements really rare?

No. They're much more abundant in the Earth's crust than many other valuable elements. Even the rarest rare earth, thulium, with atomic number 69, is . And the least-rare rare earth, cerium, with atomic number 58, is 15,000 times more abundant than gold.

They are rare in one sense, though – mineralogists would call them "dispersed," meaning they're mostly sprinkled across the planet in relatively low concentrations. Rare earths are often found in – nothing so common as basalt from Hawaii or Iceland, or andesite from Mount St. Helens or Guatemala's Volcano Fuego.

There are a few regions that are have lots of rare earths – and they're mostly in China, which produces more than 80 percent of the . Australia has a few areas too, as do some other countries. The U.S. has a little bit of area with lots of rare earths, but the last American source for them, , closed in 2015.

3. If they're not rare, are they very expensive?

Yes, quite. In 2018, the cost for an oxide of neodymium, atomic number 60, is . The price is expected to climb to $150,000 by 2025.

Europium is even more costly – about .

Part of the reason is that rare earth elements can be to get a pure substance.

4. What are rare earth elements useful for?

In the last half of the 20th century, europium, with atomic number 63, came in to wide demand for its role as a in video screens, TVs. It's also useful for absorbing neutrons in nuclear reactors' control rods.

Other rare earths are also today. Neodymium, atomic number 60, for instance, is a , useful in smartphones, televisions, lasers, rechargeable batteries and hard drives. An is also expected to use neodymium.

Demand for rare earths has , and there are no real alternative materials to replace them. As important as rare earths are to a modern technology-based society, and as difficult as they are to mine and use, the tariff battle may put the U.S. in a very bad place, turning both the country and rare earth elements themselves into pawns in this game of economic chess.

Provided by The Conversation

This article was originally published on . Read the .![]()