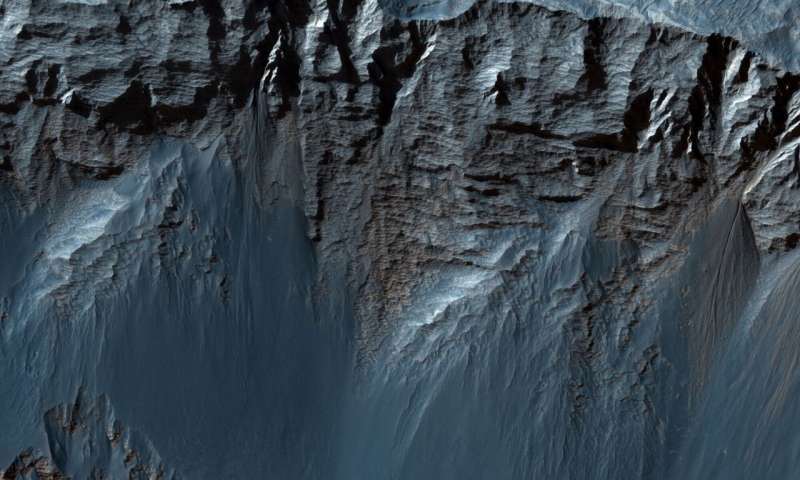

Layers upon layers of rock in Candor Chasma on Mars

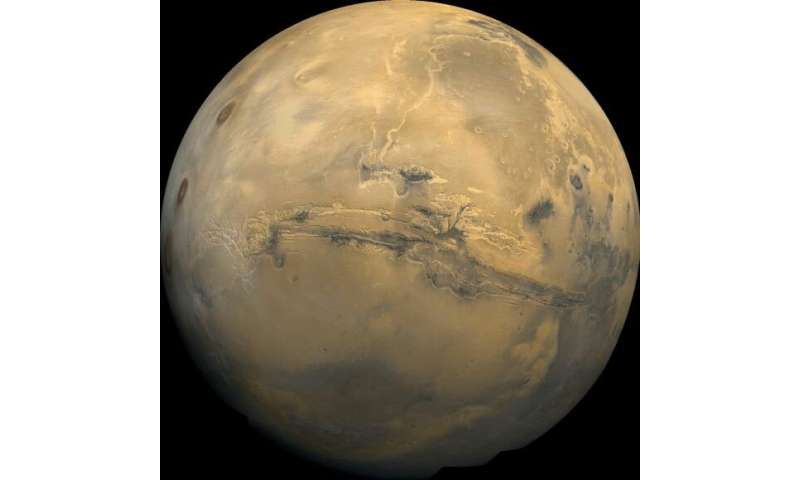

In many ways, Mars is the planet that is most similar to the Earth. The red world has polar ice caps, a nearly 24-hour rotation period (about 24 hours and 37 minutes), mountains, plains, dust storms, volcanoes, a population of robots, many of which are old and no longer work, and even a Grand Canyon of sorts. The "Grand Canyon" on Mars is actually far grander than any Arizonan gorge. Valles Marineris dwarfs the Grand Canyon of the southwestern U.S., spanning 4,000 km in length (the distance between L.A. and New York City), and dives 7 kilometers into the Martian crust (compared to a measly 2 km of depth seen in the Grand Canyon). Newly released photos from the High-Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) reveal a stunning look at eroding cliff faces in Candor Chasma, a gigantic canyon that comprises a portion of the Valles Marineris system.

at the geographic features of Candor Chasma reveals layers of sedimentary rock, helping to deepen our understanding of the depositional processes that laid these strata over billions of years. The resolution of the visible wavelength images shows details down to the scale of a single meter, allowing the visualization of rocks as small as an average golden retriever. HiRISE also observes in the near-infrared portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, and the resolution of these IR images acquires pixels a mere 30 centimeters wide, more like the size range of a toy poodle (it isn't necessary to convey resolution in terms of dogs, but it can be helpful when conveying the magnitude of such imagery to folks that are less familiar with space).

A close look at the HiRISE images shows jagged bedrock jutting out of windswept sand and dust, and also shows gully-like channels, possibly from seasonal runoff of liquid water down the sloping cliff faces. As with most finely detailed image-capture systems, HiRISE sacrifices field of view for a crisp, highly detailed look at the subject planet. In order to choose good HiRISE targets, a wider view is necessary. MRO uses another instrument with a much wider field of view to gain context from which to make scientific observation decisions. This context-gathering camera is known as the Context Camera, or CTX. CTX gives huge views of the Mars, showing large-scale geological features, painting a big picture of the planet.

-

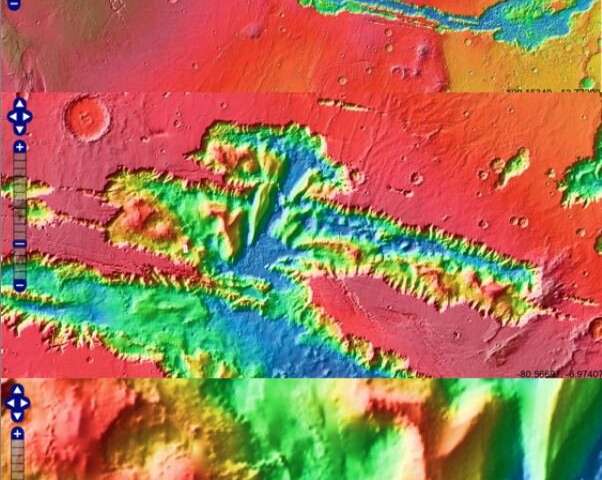

Three progressively closer looks at the HiRISE image site (represented by the white rectangle) within Candor Chasma. Credit: Google Mars -

The High-Resolution Imaging Science Experiment or HiRISE camera system (shown before flying to Mars) Credit: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona -

Valles Marineris can be seen stretching for thousands of kilometers across the face of Mars. Credit: NASA -

A broad overview of a crater on Mars taken with CTX. Oddly, smaller features within the crater have led to the appearance of a happy face. Credit: NASA/JPL/Malin Space Science Systems

This kind of broad view instrument paired with a detailed, close-up camera, is reminiscent of more down-to-Earth setups that Universe Today readers may already be familiar with. CTX can, in some ways, be thought of as a kind of finder scope like that seen on a telescope. An amateur astronomer would first use their finder scope to aim in a broad area of interest and locate a specific portion of the sky to then probe deeply with the much narrower view provided by the main telescope, or in this case, HiRISE.

By collecting broad, big-picture views, and simultaneously taking astonishingly high-resolution, close-up looks, we are gaining a better sense of the structure of Candor Chasma, Valles Marineris, and the overall geological processes and deep history of Mars. Unlike the Arizonan canyon, Valles Mariners was not formed by surface river erosion.

Which geological process could be behind the formation of the largest canyon known to humankind? Is it a dry process like the depression of a chunk of crust along parallel faults known as a graben? Another possible explanation for the formation of some features is the dissolution of rocks by subsurface water in what geologists call karst.

The watery past of Mars is a big part of what makes it such a fascinating planet to study. The Mars Perseverance Rover, already on the way and slated to land in mid-February 2021, will be landing on what is thought to be shore of an ancient Martian ocean. Large bodies of liquid water are very rare outside of the Earth, and are thought to be a necessary ingredient for the rise of living things. It goes without saying that finding evidence of life on another planet, even if it has since gone extinct, would be as impactful a scientific discovery as is possible.

Provided by Universe Today