The real Paleo diet: New archaeological evidence changes what we thought about how ancient humans prepared food

We humans can't stop playing with our food. Just think of all the different ways of serving potatoes—entire books have been written about potato recipes alone. The restaurant industry was born from our love of flavouring food in new and interesting ways.

of the oldest charred food remains ever found show that jazzing up your dinner is a human habit dating back at least 70,000 years.

Imagine ancient people sharing a meal. You would be forgiven for picturing people tearing into raw ingredients or maybe roasting meat over a fire as that is the stereotype. But our new study showed both Neanderthals and Homo sapiens had complex diets involving several steps of preparation, and took effort with seasoning and using plants with bitter and sharp flavours.

This degree of culinary complexity has never been documented before for Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers.

Before our study, the earliest known plant food remains in south-west Asia were from a in Jordan roughly dating to 14,400 years ago, reported in 2018.

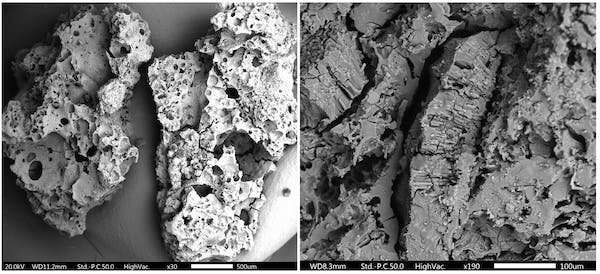

We examined food remains from two late Paleolithic sites, which cover a span of nearly 60,000 years, to look at the diets of early hunter gatherers. Our evidence is based on fragments of prepared plant foods (think burnt pieces of bread, patties and porridge lumps) found in two caves. To the naked eye, or under a low-power microscope, they look like , with fragments of fused seeds. But a powerful scanning electron microscope allowed us to see details of plant cells.

Prehistoric chefs

We found carbonised food fragments in (Aegean, Greece) dating to about 13,000-11,500 years ago. At Franchthi Cave we found one fragment from a finely-ground food which might be bread, batter or a type of porridge in addition to pulse seed-rich, coarse-ground foods.

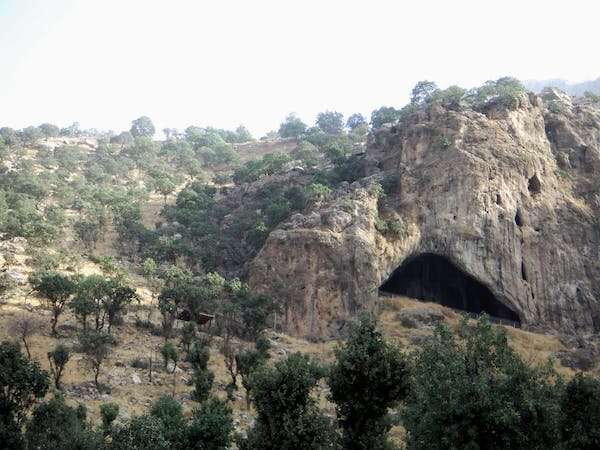

In (Zagros, Iraqi Kurdistan), associated with around 40,000 years ago and ago, we also found ancient food fragments. This included wild mustard and terebinth (wild pistachio) mixed into foods. We discovered wild grass seeds mixed with pulses in the charred remains from the Neanderthal layers. Previous studies at Shanidar found traces of grass seeds in the .

At both sites, we often found ground or pounded pulse seeds such as bitter vetch (Vicia ervilia), grass pea (Lathyrus spp) and wild pea (Pisum spp). The people who lived in these caves added the seeds to a mixture that was heated up with water during grinding, pounding or mashing of soaked seeds.

The majority of wild pulse mixes were characterised by bitter tasting mixtures. In , these pulses are often soaked, heated and de-hulled (removal of the seed coat) to reduce their bitterness and toxins. The ancient remains we found suggest humans have been doing this for tens of thousands of years. But the fact seed coats weren't completely removed hints that these people wanted to retain a little of the bitter flavour.

What previous studies showed

The presence of wild mustard, with its distinctive sharp taste, is a (the beginning of village life in the south-west Asia, 8500BC) and in the region. Plants such as wild almonds (bitter), terebinth (tannin-rich and oily) and wild fruits (sharp, sometimes sour, sometimes tannin-rich) are pervasive in plant remains from south-west Asia and Europe during the later Paleolithic period (40,000-10,000 years ago). Their inclusion in dishes based on grasses, tubers, meat, fish, would have lent a special flavour to the finished meal. So these plants were eaten for tens of thousands of years across areas thousands of miles apart. These dishes may be the origins of human culinary practices.

Based on the evidence from plants found during this time span, there is no doubt both Neanderthals and early modern humans diets included a variety of plants. Previous studies found food residues trapped in tartar on the teeth of Neanderthals from Europe and south-west Asia which show they cooked and ate such as wild barley, and . The remains of carbonised plants remains show they gathered and .

Plant residues found on grinding or pounding tools from the European later Palaeolithic period suggest and . Residues from an Upper Palaeolithic site in the Pontic steppe, in eastern Europe, shows ancient people before they ate them. Archaeological evidence from South Africa as early as 100,000 years ago indicates Homo sapiens used crushed .

While both Neanderthals and early modern humans ate plants, this does not show up as consistently in the stable isotope evidence from skeletons, which tells us about the main sources of over the lifetime of a person. Recent studies suggest Neanderthal populations in Europe were . Studies show Homo sapiens seem to have had a in their diet than Neanderthals, with a higher proportion of plants. But we are certain our evidence on the early culinary complexity is the start of many finds from early hunter-gatherer sites in the region.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons license. Read the .![]()