Researchers uncover secrets on how Alaska's Denali Fault formed

When the rigid plates that make up Earth's lithosphere brush against one another, they often form visible boundaries, known as faults, on the planet's surface. Strike-slip faults, such as the San Andreas Fault in California or the Denali Fault in Alaska, are among the most well-known and capable of seriously powerful seismic activity.

Studying these faults can help geoscientists not only better understand the process of plate tectonics, which helped form the planet's continents and mountains, but also better model their earthquake hazards. The problem is that most studies on these types of faults are (quite literally) shallow, looking only at the upper layer of the Earth's crust where the faults form.

New research led by Brown University seismologists digs deeper into Earth, analyzing how the part of the fault that's near the surface connects to the base of the tectonic plate in the mantle. The scientists found that changes in how thick the plate is and how strong it is deep into the Earth play a key role in the location of Alaska's Denali Fault, one of the world's major strike-slip faults.

The findings begin to fill major gaps in understanding about how geological faults behave and appear as they deepen, and they could eventually help lead future researchers to develop better earthquake models on strike-slip faults, regions with frequent and major earthquakes.

"That means when geoscientists model earthquake cycles, they'll have new information on the strength of the deeper rocks that would be useful for understanding the dynamics of these faults, how stress will build up on them, and how they might rupture in the future," said Karen M. Fischer, a study author and geophysics professor at Brown.

The study, published in Geophysical Research Letters, was led by Brown alumna Isabella Gama, who completed the work last year while she was a Ph.D. student in the University's Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences. The paper focuses primarily on the Denali Fault, a 1,200-mile-long fault that arcs across most of Alaska and some of Western Canada. In 2002, it was the site of a magnitude 7.9 earthquake that sloshed lakes as far away as Seattle, Texas and New Orleans.

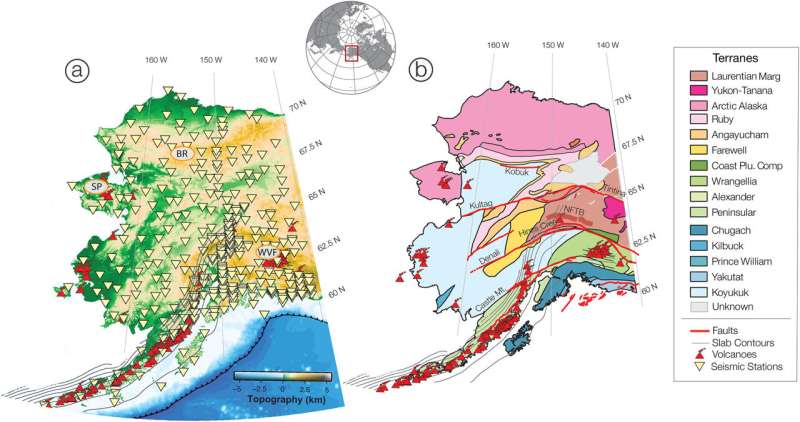

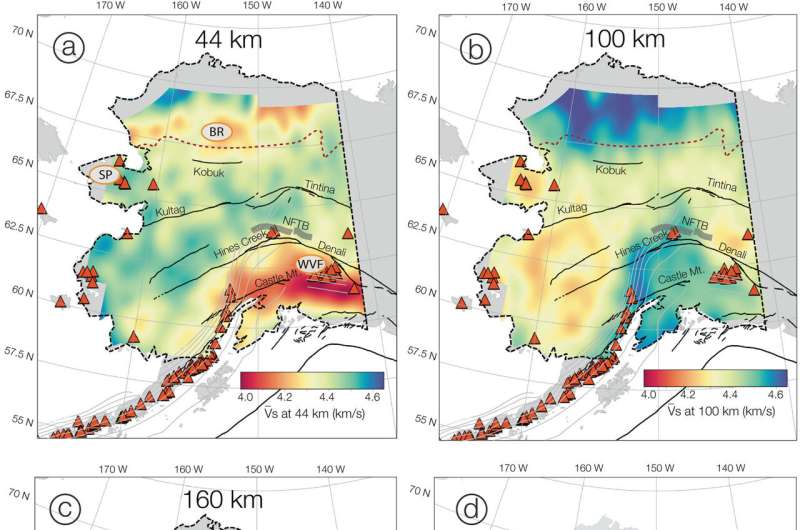

The researchers used new data from a cutting-edge network of seismic stations to create a new 3D model of seismic wave velocities throughout Alaska. With this innovative tool, the researchers discovered changes in the thickness and internal strength of the tectonic plate that Alaska sits on. The model shows how these changes in plate strength, that extend as deeply as about 80 kilometers, feed back into the mechanics of where the Denali fault line is produced.

Geoscientists have known that the Earth's crust that is south of the Denali Fault is thicker, while north of the fault, the crust is thinner. What's been less clear is data on changes in the deeper, mantle portion of the plate.

In the new study, the researchers documented for what is believed to be the first time that the Denali Fault forms because of an increase in strength on the northern side of the fault that goes all the way through the upper plate.

They found that when they looked at the base of the plate or lithosphere, the lithosphere is stronger and thicker on the northern side of the fault vs. being much thinner and weaker on the southern side. The deeper part of the plate to the north can act almost as a backstop, they describe in the paper. They conclude that the fault at the surface formed and stayed at the edge of this thicker, stronger lithosphere.

"There has been this controversy that faults in the shallower brittle crust wouldn't connect to structures in the deepest part of the plate, but here we show that they do," Gama said. "And this could mean a variety of things. For example, it means that we could expect earthquakes occurring deeper than previously thought for strike-slip faults such as the Denali fault, and that plate motions could occur on clear boundaries that extend from shallow faults all the way to the base of the plate."

The scientists' avenue of research opened up when IRIS, a research consortium dedicated to exploring the Earth's interior, deployed the EarthScope Transportable Array in Alaska from 2014 to 2021. The advanced technology—a large collection of seismographs installed temporarily at sites across the U.S.—gave researchers like Gama and Fischer the capability to measure properties of the deeper crust and mantle that hadn't been possible before.

The researchers next plan to look closer at other strike-slip fault lines around the world to see if they can find similar variations in the structure of tectonic plates the deeper they go. Other well-known strike-slip fault lines include the San Andreas Fault in California and the Anatolian Fault in Turkey, both of which have caused major earthquakes in the past. The San Andreas Fault, for instance, caused the earthquake of 1906 in San Francisco that killed thousands.

"We hope that projects such as the EarthScope Transportable Array will continue to receive support so that we can obtain higher-resolution images of the Earth's interior from anywhere on the planet," Gama said. "We hope to gain a better understanding of plate tectonics by using these images and will begin by investigating how other strike-slip faults appear and behave, looking for parallels with Alaska. This information could then be fed back into improving models for how earthquakes occur."

More information: Isabella Gama et al, Variations in Lithospheric Thickness Across the Denali Fault and in Northern Alaska, Geophysical Research Letters (2022).

Journal information: Geophysical Research Letters

Provided by Brown University