Rejecting science has a long history—the pandemic showed what happens when you ignore this

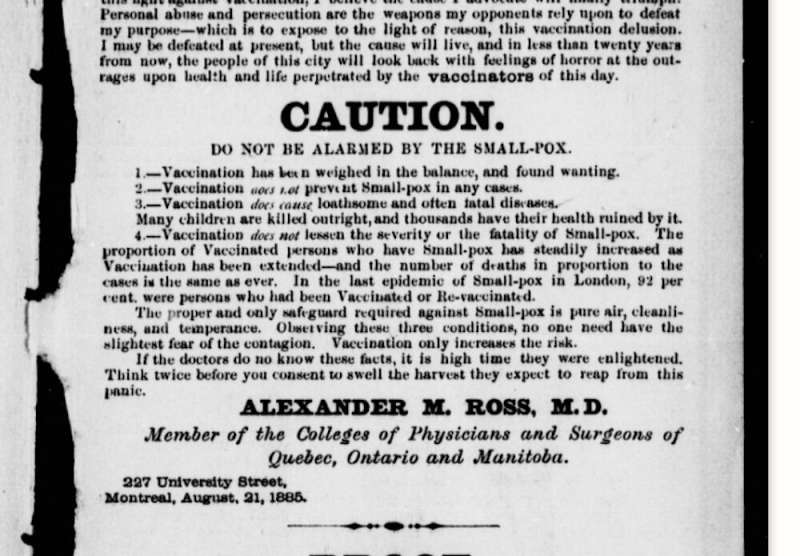

Fear engulfed everyone during the pandemic. Yet when a vaccine became available, it was . Anti-vaccination crowds formed, and some of these groups argued this vaccine was against their religious beliefs.

Many didn't trust the scientists and their explanation for how they said the disease spread. A lot of people didn't believe the , or they felt mandatory vaccinations violated their personal freedom.

also proliferated, sowing doubt about the safety of vaccines and accusing governments and .

You may think I am referring to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, I am not. This eerily familiar scenario played out when smallpox was still raging across Europe.

Anti-vaccination groups, as well as other anti-science movements, are not new phenomena, nor are the nature of their objections. Unfortunately, because history is usually when dealing with current scientific issues, people fail to acknowledge that most anti-science arguments have been .

The fact that we live in a shows these anti-science movements are also quite . And they have had a deadly impact on our society. For example, researchers found that between January 2021 and April 2022, vaccinations could have prevented at least .

Questioning the experts

A good example of how is the notion that is a new phenomenon. Yet, in 1925, a Tennessee high school teacher, John Scopes, went for teaching the theory of evolution to his students, which (due to the recent ) was considered illegal.

What became known as started as a publicity stunt by the American Civil Liberties Union, which was itching to challenge the Tennessee state's Butler Act. But it quickly turned into a face-off between an anti-evolutionist prosecutor and a defense team eager to debunk fundamentalist Christianity.

The trial ended with and handed a small fine. He is, however, still seen by many as , likely because of the .

The trial is important to science communication because of the . Seven out of eight experts were blocked from speaking (their ).

We saw a repeat of such rejection of expertise nearly a century later with COVID-19. Dr. Anthony Fauci, the most prominent US government public health spokesperson during the pandemic, was often by many members of the public, and was when he was president. Trump had paved the way for this by pronouncing that during his 2016 presidential campaign.)

Fauci was even falsely accused of funding research to and of to become rich from COVID vaccines. All this is likely to have responded to Fauci's crucial information during the pandemic.

Expertise, trustworthiness, and objectivity are the components that . So when scientists are portrayed as biased, the effectiveness of their communication .

Treating skeptics with disrespect achieves nothing

Most scientists , which can leave them unprepared for online showdowns over contested science. Take the immunologist Roberto Burioni as an example. In 2016, he caused a row when he deleted all comments relating to a Facebook discussion about vaccination. Burioni added a that read:

"Here only those who have studied can comment, not the common citizen. Science is not democratic."

This post did attract some but also and alienated countless people.

Of course, problem can feel overwhelming. And partly since some research suggests countering falsehoods ), experts often avoid these .

However, a growing body of work suggests correcting misinformation . The because a standard explanation may not fit everyone.

A fork in the road

Many scientists have an aptitude for engaging the public. science TV host Emily Calandrelli and Robert Sapolsky have captured the imaginations of millions of people with no background in science.

The Oliver Sacks was known as the "poet laureate of medicine" for his work writing about poorly understood conditions such as Tourette's syndrome and autism. There are science YouTube channels with of subscribers and .

But the smallpox protests and the Scopes trial are . History can help scientists reevaluate how they communicate, stop repeating mistakes, and form better relationships with the public.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons license. Read the .![]()