Coral reefs: How climate change threatens the hidden diversity of marine ecosystems

Like the heat waves on land we have all grown familiar with, are being . These extreme warm water events have of climate change and are now a major threat to ocean life.

Coral reefs, which are . This is a dire situation, given the vast number of people who for their sustenance and livelihoods.

As climate change pushes corals beyond their limits, a key question is to warm waters.

In our , we examined the genetics of hundreds of individual corals during the 2015–16 El Niño-driven heat wave. Our results suggest that heat waves have hidden impacts on the genetic composition of reef-building corals. Understanding this could help scientists bolster reef resilience to future heat waves.

Pushing corals out of their comfort zones

Corals are of their local waters, with temperatures even 1°C warmer than normal pushing them out of their comfort zone.

Unusually warm water between stony corals (the reef-builders) and their symbiotic partners, microscopic algae that provide food to the corals. This causes coral bleaching, and in many cases mortality.

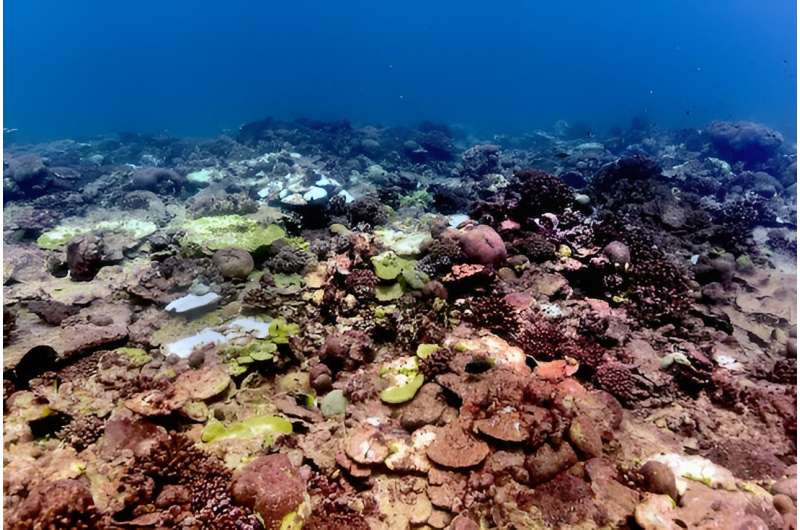

The tropical heat wave at our study site in the central Pacific Ocean, Kiritimati (Christmas Island), lasted for ten months, a world record. This led to extensive coral bleaching, presenting an opportunity to determine why some corals died and others survived.

Cryptic diversity within a widespread coral species

We focused on the widespread lobed coral (Porites lobata). This species is among the most heat-tolerant corals, and despite on Kiritimati, over half of lobed corals survived.

In fact, some Porites colonies didn't bleach at all.

Why?

Using genomic tools, we identified three distinct types of Porites lobata on Kiritimati. These lineages, which may represent distinct species, are indistinguishable by eye but genetically different.

Such biodiversity is known as Although cryptic diversity is widespread across corals, its ecological implications remain unclear.

Marine heat waves threaten cryptic diversity

We found that one genetic lineage of Porites was highly sensitive to the heat wave: only 15% of its colonies survived compared to 50%–60% in the other lineages. Thus, even in a coral widely considered to be stress tolerant, heat waves can have hidden impacts, threatening diversity that is invisible to the naked eye.

If future marine heat waves continue to have similar effects, eventually sensitive genotypes like this one could be completely lost, reducing the genetic diversity of coral reefs.

Because interbreeding between cryptic lineages and species can offer a , losses of genetic diversity could make a bad problem even worse by limiting future adaptation to changing environments.

A forced breakup

So why did Porites lineages on Kiritimati differ in survival?

One hypothesis is that they house symbiotic partners with different heat sensitivities. Using metabarcoding, a technique that attempts to identify everything found living in the coral tissue, we identified which symbionts were partnered with which corals before, during and after the heat wave.

We found that the distinct Porites lineages had different partnerships before the heat wave. Porites species pass on their symbionts from and so these relationships likely arose over many generations.

By the end of the heat wave, however, one of Porites' unique algal partners had been virtually eliminated. The survivors of all lineages had similar symbionts, suggesting specialized relationships between the partners had been lost under extreme temperatures.

Thus, not only was a cryptic coral lineage left teetering on the edge of local extinction, but its specialized symbiotic relationship had also been forcefully broken up.

Implications for conserving coral reefs

Due to climate change and other threats, we are currently experiencing a . Our findings underscore that this crisis extends beyond what the eye can see.

Cryptic species often occupy . Discovering these hidden differences can enhance our understanding of how ecosystems function. But worryingly, we may be losing this critical diversity before it is even discovered.

Continued study of cryptic diversity could prove essential to building climate resilient ecosystems. Using heat tolerant cryptic lineages in , for example, could help make reefs more tolerant to future warming.

Ultimately, . While targeted efforts to bolster coral reefs against climate change may buy limited time, the current heat waves blanketing the world's oceans underscore that the ocean is simply becoming too hot for corals and we need to act rapidly to mitigate the damage.

Journal information: Science Advances

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons license. Read the .![]()