Iowa State researcher studies how enzymes break down cellulose

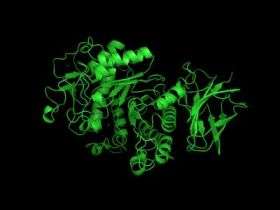

Peter Reilly pointed to the framed journal covers decorating his office. Each of the six showed the swirling, twisting, complicated structure of an enzyme. Those bright and colorful illustrations are the work of his lab. And they’re part of Reilly’s work to understand how the structure of an enzyme influences its mechanism and its activity.

In other words, he’s trying to figure out “how is it that these things work,” said Reilly, a professor of chemical and biological engineering and an Anson Marston Distinguished Professor of Engineering at Iowa State University.

That’s important because enzymes do a lot for all of us.

Enzymes are proteins produced by living organisms that accelerate chemical reactions. They, for example, work inside the human digestive system to break starch or protein molecules into smaller pieces that can be absorbed by the intestines. Enzymes are also used to produce bread, they’re added to detergents to clean stains and they’re used to treat leather. And because enzymes break down cellulose into simple sugars that can be fermented into alcohol, they’re a big part of producing ethanol from cellulose.

Reilly is particularly interested in the enzymes that work on cellulose. He has a three-year, $306,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to develop a basic understanding of how they work.

Those enzymes are known as cellulases. They’re commonly produced by fungi and bacteria. And they’ve got a very hard job.

Cellulose is tough stuff. It’s in the cell walls of plants. It’s what gives a plant its structure.

“It’s why trees stand up,” Reilly said.

He also said, “Nature has done its best to break down cellulose.”

So different enzymes have developed different ways of attacking cellulose.

One enzyme Reilly has studied and illustrated – a cellobiohydrolase enzyme – has an extension that works like a little plow. It rips up one cellulose chain from a cellulose crystal and feeds it into a tunnel on the main enzyme surface so that it can be chopped up.

Reilly, who can’t resist a lesson in biochemistry, likes to explain how enzymes attack and break chemical bonds. He’ll display diagrams on his office computer that show the bonds in cellulose molecules. He’ll point out where enzymes attack some of those bonds. He’ll say the chemical reactions create high-energy transition states that scientists are working hard to understand. And he’ll get back to the bottom line.

“These different enzymes all do the same thing,” Reilly said. “They all break down bonds between the sugars that make up cellulose.”

And, he said, “For something that’s not alive, enzymes are awfully sophisticated.”

Reilly’s students use a lot of computing power to figure out how enzymes are put together. They routinely work with CyBlue, Iowa State’s supercomputer capable of 5.7 trillion calculations per second, and Lightning, an Iowa State high-performance computer capable of 1.8 trillion calculations per second.

By adding to the basic understanding of enzymes, Reilly is opening doors for new and better applications of enzymes. Better enzymes, for example, could be the key to making the production of cellulosic ethanol more efficient and more economical.

There’s still a lot for chemical engineers to learn about the specialized proteins.

After all, Reilly said, “Nature has tried over and over to find ways to break down cellulose.”

Source: Iowa State University