Bringing life into focus

Spinning-disk confocal microscopy is an optical imaging technique that can be used to generate detailed three-dimensional fluorescence images of living cells and their contents. Although a powerful tool for observing dynamic processes in living organisms, it has proved difficult to use for all but the thinnest biological specimens. Motivated by a need to see more deeply into living cells, Yuko Mimori-Kiyosue at the RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology and colleagues have now made major technical improvements to the technique that deliver greatly improved resolution and clarity.

Mimori-Kiyosue's team conducts research on cellular structures called microtubules. Visualizing their dynamic behavior and arrangement in live mice proved frustrating. "We didn't have a microscope that enabled imaging of fast-moving, submicrometer-sized structures in cells within thick specimens," she says.

In confocal microscopy, a laser scans a fluorescently labeled sample and the emitted fluorescence is observed through a pinhole that blocks most of the out-of-focus light. Although the technique is able to generate sharp three-dimensional reconstructions, the scanning process is too slow for use on living cells. The spinning-disk method accelerates the process through the rotation of a disk containing many pinholes, which splits the laser into multiple beams. Unfortunately, this approach is limited by 'pinhole cross-talk'—the unwanted intrusion of background fluorescence through adjacent pinholes. Pinhole cross-talk becomes particularly severe in thick tissue samples due to high background levels.

The researchers overcame this problem with a strategy known as 'two-photon illumination', which generates fluorescence only within the focal plane of the image. While background signal is eliminated, the strategy does require the use of more powerful lasers. In response, they developed new spinning-disk units with special microlenses that efficiently condensed laser light, with pinholes spaced further apart to further minimize cross-talk.

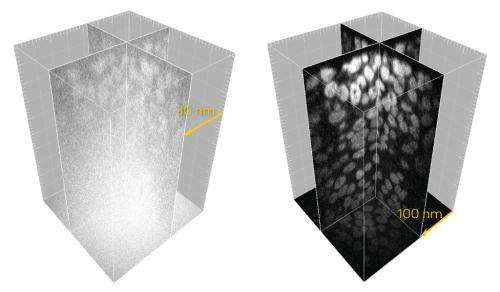

When combined with a more sensitive high-resolution digital camera, these modifications yielded remarkably improved image quality (Fig. 1), allowing the research team to clearly image the dynamic behavior of microtubules in fruit fly and worm embryos as well as mouse oocytes at depths of up to 100 micrometers. The researchers now intend to use the technique to investigate genetically modified mice expressing fluorescently tagged microtubule-associated proteins.

The maximum tissue depth and sample area that can be imaged by this technique are currently limited by the power of the lasers used, but such limitations are anticipated to be short-lived. "Following the development of the next generation of high-powered lasers, we expect this system to have a large impact in the field of life sciences," Mimori-Kiyosue says.

More information: Shimozawa, T. et al. Improving spinning disk confocal microscopy by preventing pinhole cross-talk for intravital imaging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 110, 3399–3404 (2013).

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Provided by RIKEN