Unprecedented Arctic warmth in 2016 triggers massive decline in sea ice, snow

A new NOAA-sponsored report shows that unprecedented warming air temperature in 2016 over the Arctic contributed to a record-breaking delay in the fall sea ice freeze-up, leading to extensive melting of Greenland ice sheet and land-based snow cover.

Now in its 11th year, the , released today at the annual American Geophysical Union fall meeting in San Francisco, is a peer-reviewed report that brings together the work of 61 scientists from 11 nations who report on air, ocean, land and ecosystem changes. It is a key tool used around the world to track changes in the Arctic and how those changes may affect communities, businesses and people.

"Rarely have we seen the Arctic show a clearer, stronger or more pronounced signal of persistent warming and its cascading effects on the environment than this year," said Jeremy Mathis, director of NOAA's Arctic Research Program. "While the science is becoming clearer, we need to improve and extend sustained observations of the Arctic that can inform sound decisions on environmental health and food security as well as emerging opportunities for commerce."

Major findings in this year's report include:

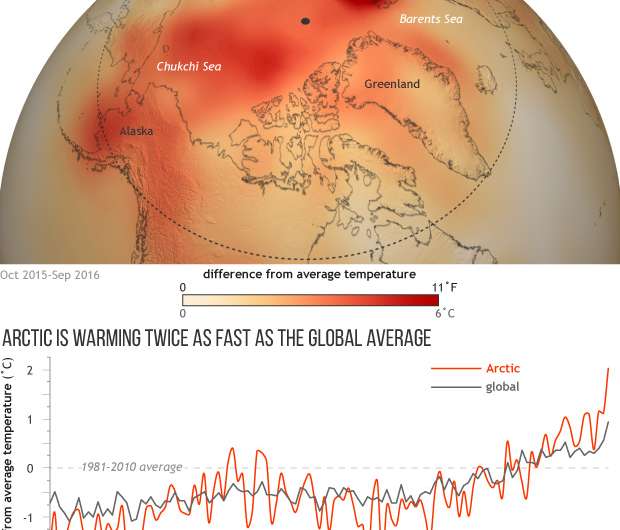

- Warmer air temperature: Average annual air temperature over land areas was the highest in the observational record, representing a 6.3 degree Fahrenheit (3.5 degree Celsius) increase since 1900. Arctic temperatures continue to increase at double the rate of the global temperature increase.

- Record low snow cover: Spring snow cover set a record low in the North American Arctic, where the May snow cover extent fell below 1.5 million square miles (4 million square kilometers) for the first time since satellite observations began in 1967.

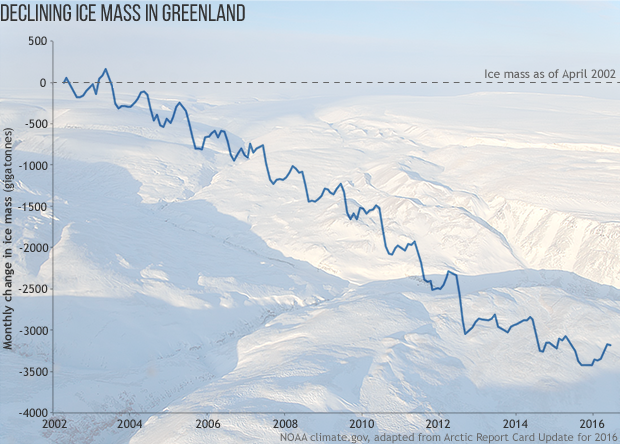

- Smaller Greenland ice sheet: The Greenland ice sheet continued to lose mass in 2016, as it has since 2002 when satellite-based measurement began. The start of melting on the Greenland ice sheet was the second earliest in the 37-year record of observations, close to the record set in 2012.

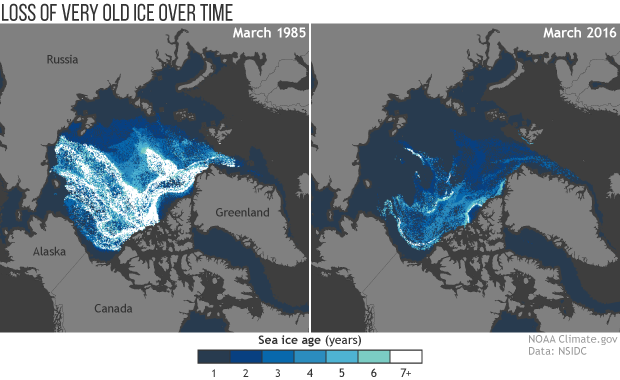

- Record low sea ice: The Arctic sea ice minimum extent from mid-October 2016 to late November 2016 was the lowest since the satellite record began in 1979 and 28 percent less than the average for 1981-2010 in October. Arctic ice is thinning, with multi-year ice now comprising 22 percent of the ice cover as compared to 78 percent for the more fragile first-year ice. By comparison, multi-year ice made up 45 percent of ice cover in 1985.

- Above-average Arctic Ocean temperature: Sea surface temperature in August 2016 was 9 degrees Fahrenheit (5 degrees Celsius) above the average for 1982-2010 in the Barents and Chukchi seas and off the east and west coasts of Greenland.

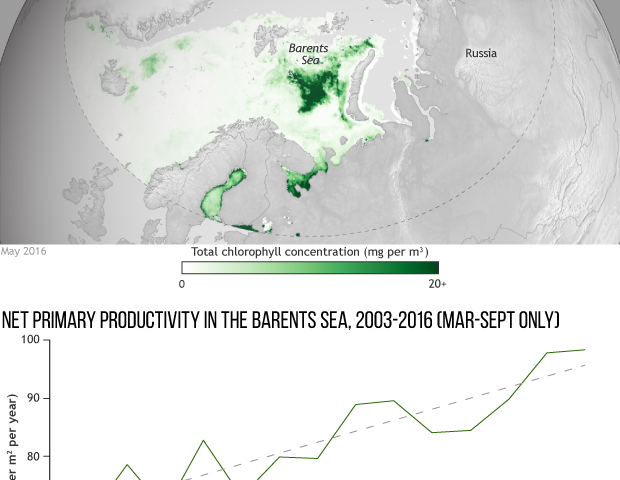

- Arctic Ocean productivity: Springtime melting and retreating sea ice allowed for more sunlight to reach the upper layers of the ocean, stimulating widespread blooms of algae and other tiny marine plants which form the base of the marine food chain, another sign of the rapid changes occurring in a warming Arctic.

This year's report also includes scientific essays on carbon dioxide in the Arctic Ocean, on land and in the atmosphere, and changes among small mammals.

- Ocean acidification: More than other oceanic areas, the Arctic Ocean is more vulnerable to ocean acidification, a process driven by the ocean's uptake of increased human-caused carbon dioxide emissions. Ocean acidification is expected to intensify in the Arctic, adding new stress to marine fisheries, particularly those that need calcium carbonate to build shells. This change affects Arctic communities that depend on fish for food security, livelihoods and culture.

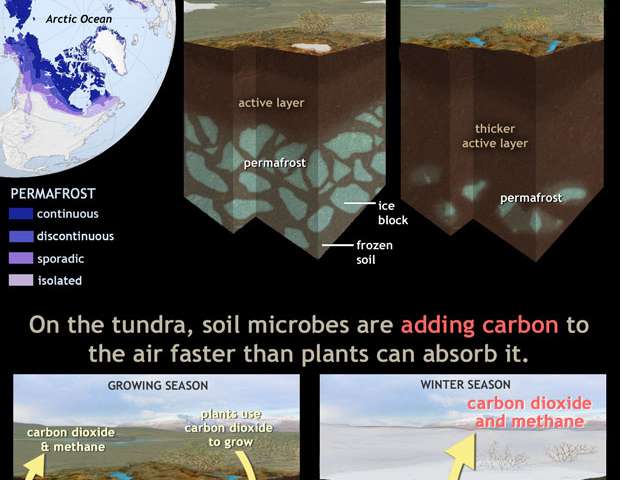

- Carbon cycle changing: Overall, the warming tundra is now releasing more carbon into the atmosphere than it is taking up. Twice as much organic carbon is locked in the northern permafrost as is currently in the Earth's atmosphere. If the permafrost melts and releases that carbon, it could have profound effects on weather and climate in the Arctic and the rest of the Earth.

- Small mammals: Recent shifts in the population of small mammals, such as shrews, may be the signs of broader consequences of environmental change.

-

The age of the sea ice in the Arctic Ocean at winter maximum in March 1985 (left) compared with March 2016 (right). The darker the blue, the younger the ice. The first age class on the scale (1, darkest blue) means "first-year ice,” which formed in the most recent winter. The oldest ice (7+, white) is ice that is more than seven years old. Historically, most of the ice pack was many years old. Today, only a fraction of that very old ice reamins. NOAA Climate.gov maps, based on NOAA/NASA data provided by Mark Tschudi. Credit: NOAA Headquarters -

(map) Total chlorophyll concentration across the Artic in May 2016. The darker the green, the higher the chlorophyll concentration. The light gray indicates areas where there was no data due to clouds or ice. In some areas, chlorophyll concentrations averaged more than 14 milligrams per cubic meter higher than the 2003-2015 mean. (graph) Net primary productivity (the net carbon gain or loss by growing plants) in the Barents Sea for March-September 2003-2016. NOAA Climate.gov map derived from NASA/MODIS-Aqua data. Graph adapted from Figure 6.4 in the 2016 Arctic Report Card. Credit: NOAA Headquarters -

(map) Stretching from Alaska to Scandinavia to Russia, and hundreds of feet deep in places, the Arctic's frozen soils--permafrost--contain twice as much carbon as what's already in the atmosphere. As the Arctic heats up, permafrost may become a major source of greenhouse gases, which would further accelerate global warming. (top middle) Permafrost is like a giant freezer for carbon: thousands of years worth of plant, animal, and microbe remains mixed with blocks of ice. Historically, only a shallow "active layer" thawed in the short summer. (top right) In today's warming Arctic, permafrost is thawing and the active layer is getting deeper. (bottom left) Warming in the growing season has increased plant growth and allowed plants to remove more carbon dioxide (CO2) from the air during photosynthesis, but it is also thawing the frozen soils and stimulating decomposition of organic matter by soil microbes. Microbial activity releases the greenhouse gases CO2 and methane (CH4). (bottom right) When winter comes, the uppermost soil layer re-freezes quickly as air temperatures drop. But deeper layers, insulated from the frigid air, re-freeze more slowly. In the past decade, the parts of the Arctic tundra that are routinely observed have become a net source of carbon-containing greenhouse gases because microbial activity is continuing well into winter after plants go dormant. Credit: NOAA Climate.gov drawing. Permafrost map from NSIDC

Provided by NOAA Headquarters