CO2 shortage—why can't we just pull carbon dioxide out of the air?

More people than ever are acutely aware that rising levels of carbon dioxide (COâ‚‚) in the atmosphere are accelerating climate change and global warming. And yet food manufacturers have been issuing stark warnings that they've nearly run out of the gas, which is used in many products from . The obvious question is: why we can't just capture the excess COâ‚‚ from the atmosphere and use that?

It is actually possible to take COâ‚‚ from the atmosphere using a process known as direct air capture. Indeed, there are a number of companies across the world, including and , that can . In theory, it could turn a problem into a valuable resource, particularly in developing countries with little other natural wealth.

The problem is the cost. While the amount of COâ‚‚ in the air is damaging the climate, relatively speaking there are so few COâ‚‚ molecules in the air that sucking them out is very expensive. But there may be other solutions that could help reduce carbon emissions and provide a new source of COâ‚‚ for industry.

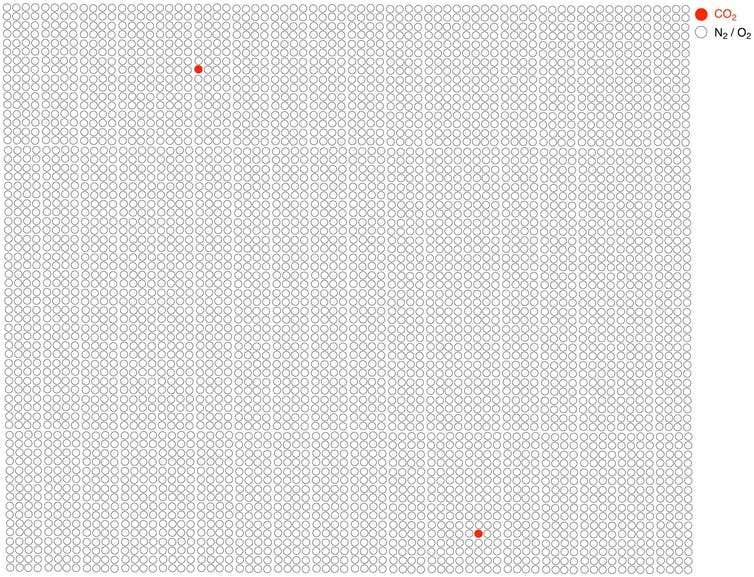

It's all a matter of concentration and energy consumption. The amount of COâ‚‚ in the air (which is mostly made up of nitrogen and oxygen) is around or 0.04%. If we were to represent a sample of molecules from the air as a bag of 5,000 balls, just two of them would be COâ‚‚. Pulling them out of the bag would be very difficult.

We can capture COâ‚‚ using what's known as a sorbent material that either physically interacts or bonds with the gas at a molecular level. To capture a viable amount of COâ‚‚ from the air, we would need to compress huge amounts in order to pass it through the sorbent, something that would require a lot of energy.

The exhaust of power stations is a more concentrated source of COâ‚‚ (and one responsible for so much of our total carbon emissions). The Carbon XPRIZE, a competition to encourage the development of carbon capture and utilisation technology, has identified that focus on capturing COâ‚‚ from power plants rather than the atmosphere.

Yet while the typical COâ‚‚ concentration of (600 balls out of the 5,000) in power station exhaust is much greater than that of air, capturing the COâ‚‚ would still be a costly way of purifying the gas using current technologies. You also need to remove the water vapour in the exhaust, which would require .

Better sources

As it becomes more important to reduce the concentration of COâ‚‚ in the atmosphere, or if you needed to produce the gas in remote locations with large renewable energy sources, direct air capture could become a viable technology. But at the moment there are COâ‚‚ sources that are more concentrated and so .

For example, distilleries and breweries produce the gas as a waste product with high purity (over 99.5%) once any water has been removed. Cement works, steel works and other process industries also have relatively high . Building smaller facilities that just capture the COâ‚‚ from individual factories and plants would be a cheaper way to create a new source of the gas. They may also prove a good investment at plants that need their own supply of COâ‚‚ to carry out their processes.

The current COâ‚‚ shortage is mainly affecting the food and drink industry. But we're also starting to see a greater push to use COâ‚‚ in other industries as a way of creating a market for a substance that is otherwise a waste product contributing to dangerous climate change. You can now buy chemicals and building materials that started life as COâ‚‚ molecules instead of fossil fuels, for example, including mineral aggregates that actually capture more carbon than is .

As more of these COâ‚‚ utilisation technologies emerge, demand for the gas will increase and so will the need for more localised production. The future is about turning a waste into a commodity.

Provided by The Conversation

This article was originally published on . Read the .![]()