The nose of E. coli zips open and closed

With ice-cold electron microscopy microbiologists from Leiden gain more insight into how bacteria respond to their environment. Publication in mBio.

For their discovery Ph.D.-student Wen Yang and her colleagues used a cryo-electron microscope at the Netherlands Centre for Electron Nanoscopy (NeCEN) in Leiden. Inside the microscope the temperature is almost 200°C below zero. By freezing microbes very quickly they are pristinely preserved in a glass like ice. With the use of cryotomography the researchers are able to resolve the microbes in 3-D and in more detail than a usual electron microscope would allow. The team led by professor Ariane Briegel has taken hundreds of photos of a harmless strain of the Escherichia coli bacterium containing different activation stages of the receptors that "smell" their chemical environment. After previous discoveries by Briegel about the "nose" of bacteria, they have now learned more about how the signal travels from the "nose" to the "tail" (flagellum) that allows bacteria to move in a targeted manner.

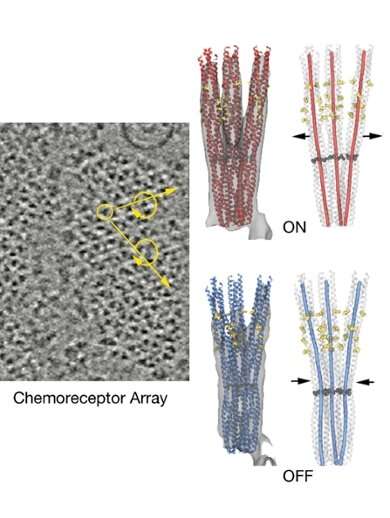

The chemoreceptors that form the "nose" of the E. coli are only a few nanometers in size and are arranged in a highly ordered hexagonal lattice pattern (image left). Receptors (images right) protrude from the bacterium envelope into the inside of the cell. They form a connection between the inner world of the bacterium and the environment. The researchers have discovered that depending on the type of molecules that bind on the outside, a certain amino acid hinge allows the receptor to zip up or be in a more open state (images top and bottom right), while maintaining the hexagonal structure. This allows for signal propagation in the bacterium with the aim of controlling the movement of the E. coli.

Bacteria use chemotaxis to respond to their environment. They move as a result of the concentration of certain substances in their surroundings, for example to search for food sources or to leave an unfavorable environment. Briegel: "Chemotaxis also plays an important role in the first steps of host invasion for pathogenic bacteria. Understanding it might help in the development of new antimicrobial agents."

Journal information: mBio

Provided by Leiden University