From Shark Bay seagrass to Stone Age Scotland, we can now assess climate risks to World Heritage

Climate change is the . However, no systematic approach to assess the climate vulnerability of each particular property has existed—until now.

Our newly developed tool, the , was showcased this week at the . This CVI provides a systematic way to rapidly assess climate risks to all types of World Heritage properties—natural, cultural and mixed.

We have successfully trialled this approach for two very contrasting World Heritage properties: and the , a late Stone Age settlement and series of monuments off mainland Scotland's north coast.

Hundreds of World Heritage properties are already being significantly impacted by climate change. , , , , , are all being affected.

In most cases, climate change results in a deterioration in a property's "Outstanding Universal Value"—the set of characteristics that led to it being internationally recognised as World Heritage in the first place.

The severity of the current climate impacts varies widely between different properties, as does the timescale over which the damage is occurring. In many places, we can expect climate-related deterioration to accelerate in the future.

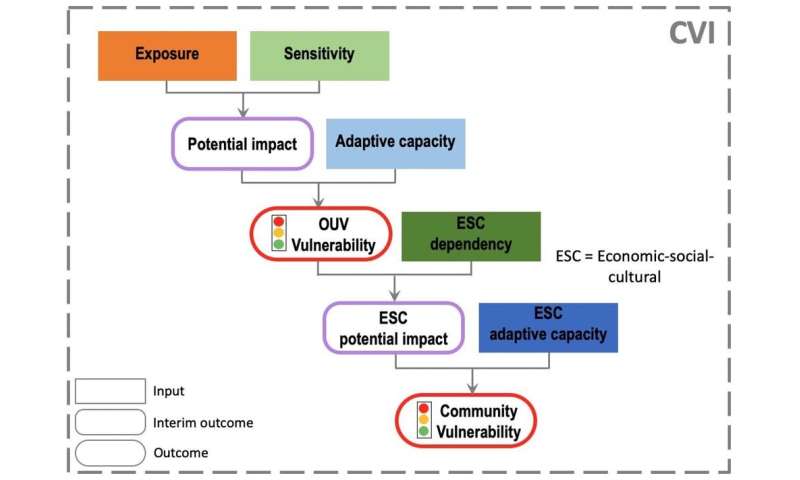

The Climate Vulnerability Index

The CVI applies a risk-assessment approach that builds upon an existing vulnerability framework used by the . However, ours is the first such tool specifically customised for application to World Heritage properties and their associated communities.

In assessing a particular property, we look first at the , which highlights the internationally recognised characteristics. The vulnerability to physical climate drivers (such as sea level rise) is then assessed, identifying three key drivers most likely to impact those values over an agreed timescale (for instance, by 2050).

The next stage is to evaluate the "Community Vulnerability"—the level of economic, social and cultural risk to the associated community, and its capacity to adapt to future changes.

The whole process is best undertaken in a 2-3 day workshop. Ideally, this includes heritage managers, community members, associated businesses, academics, and other stakeholders.

The aim is to provide guidance that is scientifically robust and practical. Because the workshops are relatively short, they can be periodically repeated as part of management processes. This is important given the rapid pace of climate change.

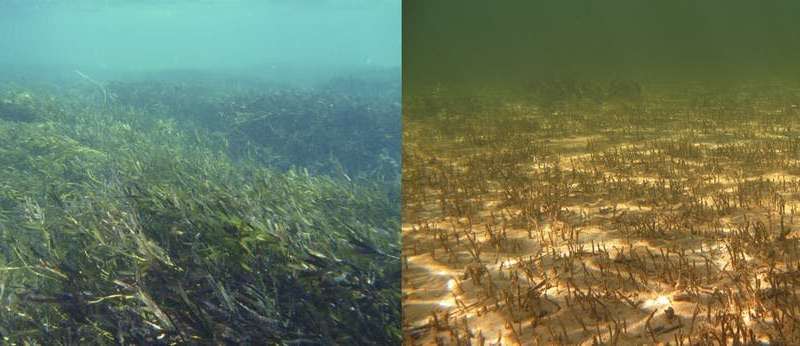

Key climate drivers determined for Shark Bay were extreme marine heat events, storm intensity and frequency, and air temperature change. Storm intensity and frequency was also identified for , along with sea-level rise and precipitation change.

-

he Climate Vulnerability Index framework. , Author provided -

Seagrass before (left) and after (right) the 2015 die-off in Shark Bay, Western Australia resulting from an extreme marine heat event. Credit: Matthew Fraser -

Damage to the footpath resulting from higher visitor numbers and increased rainfall levels at the Ring of Brodgar, part of the Scottish World Heritage property, Heart of Neolithic Orkney. Credit:

Where to next?

The CVI method is currently in a pilot phase, but the two trials so far have successfully demonstrated its value as a rapid yet robust assessment tool. has recommended that the CVI be applied to other Scottish World Heritage properties and repeated at five-yearly intervals in parallel with management plan reviews.

Meanwhile, planning is underway for further trial assessments in the , a network of tidal mud flats along Europe's northwest coast, and Norway's . International colleagues have also proposed trials in Africa and South America.

Scientifically robust, transparent and repeatable assessments will be increasingly important for managing all types of threatened heritage in the face of climate change, and for prioritising actions within World Heritage processes.

Almost all parties to the World Heritage Convention have signed or ratified the . However, the current global trajectory will not achieve the goal to keep global temperature rise well below 2℃ above pre-industrial levels. Immediate and significant action on the causes of climate change is critical. Our new tool can help governments better understand the implications of climate change for the heritage for which they are individually and collectively responsible, and can help them respond in a more strategic way.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons license. Read the .![]()