Tsetse flies nurse their young, and understanding this unusual strategy could help fight the disease they spread

Tsetse flies are bloodthirsty. Natives of sub-Saharan Africa, tsetse flies can transmit the microbe Trypanosoma when they take a blood meal. That's the protozoan that causes ; without treatment, it's fatal, and millions of people are at risk due to the bite of a tsetse fly.

focuses on insects that feed on the blood of people and animals. From a human health standpoint, understanding what makes all these bugs tick is key to developing ways to control them and prevent transmission of the diseases they carry, such as malaria, dengue, Lyme disease, West Nile virus and many others.

Tsetse flies stand out from their blood-feeding cousins the mosquitoes and ticks because of their unique reproductive biology. They give birth to live young and, even more unusual, the mother lactates and provides milk for her offspring. Here's how it all works—and why their unusual reproduction strategy might be a key to controlling tsetse flies and the parasite they carry once and for all.

From egg to larva

Scientists know of other flies that hold onto their eggs in their reproductive tract until they hatch into young larvae, with each brood consisting of dozens of offspring. The mother then tries to find a suitable source of nutrition in the environment, and leaves them to survive on their own. The mother does not provide any nutrition for her young.

That's the standard fly way of life. .

Female tsetse flies develop . When the egg is complete, the mother moves it from her ovaries into her uterus in a process called ovulation. Once in the uterus, the egg is fertilized with sperm the female has stored in an organ called the spermatheca. While females can mate multiple times, they obtain all the sperm they need for their lifetime from a male fly during a single mating event.

After fertilization, the for five days while an embryo develops within the egg. When the embryo is ready, the egg hatches in the uterus of the female and the tsetse fly larva begins its life .

Milk meals for baby

Here's where tsetse flies dramatically diverge from most other insects.

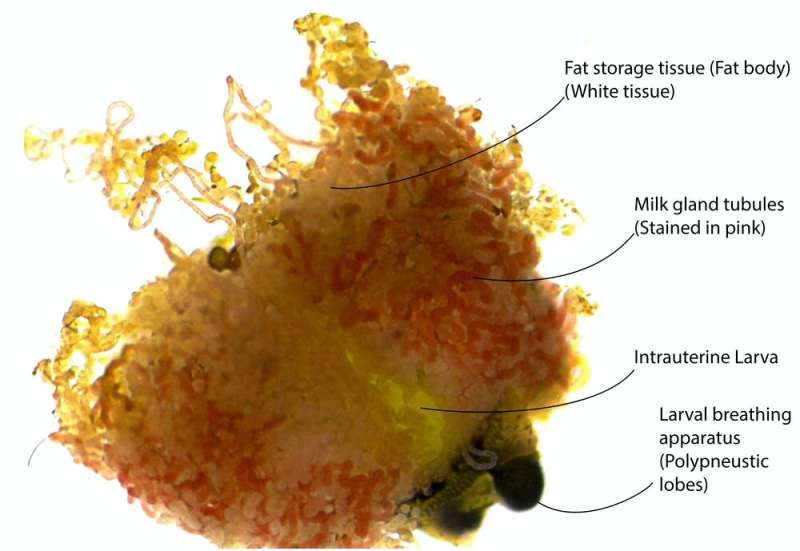

Attached to the mother's uterus is a . The organ is called the milk gland, and it produces a rich mixture of fats and particular proteins that provide the larva with all the nutrition it needs to develop into an adult.

Amazingly, many are to those found in the milk produced by mammals.

Just like in mammals, the milk also from the mother to the offspring. for tsetse flies, and without them .

After five or six days of developing and feeding on milk, the larva is fully grown and ready to enter the world. The mother finds a safe spot and gives birth. The larva immediately burrows underground to avoid predators and parasites.

Once buried, the outer surface of the larva's skin hardens and turns black, forming a protective shell. This is called the pupal stage and it lasts for around three weeks. During this time, the pupa transforms into an adult fly.

It then emerges from the pupa, climbs out of the ground, and begins its life as an adult tsetse fly looking for hosts to blood-feed on and other tsetse flies to mate with.

Why live birth?

Why would an insect evolve this slow and resource-intensive way to reproduce?

One idea is that this method provides a defensive advantage relative to free-living larvae against parasites and predation. Larvae on their own have few (if any) ways to defend against these threats. But keeping larvae in the mother's uterus provides shelter and a guaranteed food source. While this strategy is much slower, scientists think the extra maternal care results in . It's a matter of quality over quantity.

A result of this reproductive strategy is that tsetse fly populations are small and slow to recover from control efforts, relative to more prolific insects like mosquitoes.

My colleagues and I hope that we can parlay our understanding of the molecular processes that regulate tsetses' milk production and mating behavior into new environmentally friendly, cost-effective and tsetse-specific control strategies for these insects.

The sleeping sickness tsetse flies spread is a potential issue for , though the number of annual cases has decreased drastically thanks to major control efforts—including trapping flies, applying insecticides and where they mate with wild females but don't produce offspring. Ultimately, we'd like to contribute to the World Health Organization's goal of with a new way to prevent the transmission of disease-causing trypanosomes to people and animals.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons license. Read the .![]()