10 reasons to stop whipping racehorses, including new research revealing the likely pain it causes

Pressure is on the global horse-racing industry to reconsider the use of whips in the sport.

Our research, published in the journal , shows horses' skin is very similar to humans' in both thickness and the arrangement of nerve endings.

This adds to existing evidence that whipping is ineffective and unethical. Here we outline ten reasons why it's time to drop the crop.

1. Horses' skin appears just as sensitive as humans'

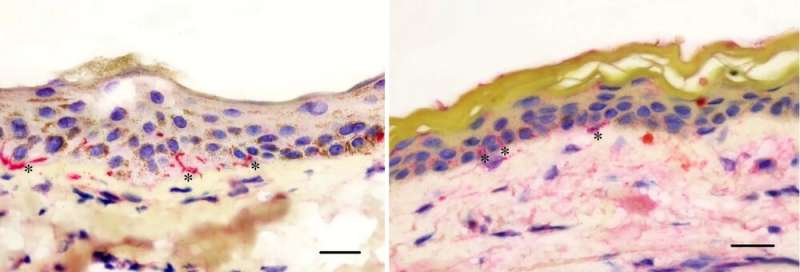

At the core of the debate is the question of whether horses experience pain when being whipped. A Sydney-based research team (of which one of us, Paul McGreevy, was a member) examined skin from 10 human cadavers and 20 euthanased horses under a microscope to explore any differences in their skin structure and nerve supply.

The results revealed no significant difference between humans and horses in the concentration of nerve endings in the outer, surface layer of skin.

2. Horses' skin is no thicker than humans'

The new study also found no significant difference between humans and horses in the average thickness of this outer layer.

Horses need skin that is both robust and sensitive to touch, particularly from other horses or flying insects. The inner, base layer of skin in humans is significantly thinner than in horses, but this is not where the nerve endings lie.

3. Whip-free racing already exists

Norway outlawed the whipping of racehorses in . In the United Kingdom, have been part of the racing calendar since 1999. These events, in which the least experienced (and presumably most vulnerable) jockeys race without using the whip, is at complete odds with the industry's contention that whips are essential for steering and safety. There are no reports from Norway or the UK of problems in the conduct of these races.

4. There's no evidence whips make racing safer…

Whip use has been claimed to be essential for the safety of horses and jockeys. However, the impact of whip use on steering and safety had not been examined until a compared "whipping-free" races, in which whips are held but not used, with "whipping-permitted" races.

Races of these two types were meticulously matched for racecourse, distance, number of runners, and "going" (turf conditions on the day). A detailed examination of stewards' post-race reports revealed no difference between the two race types in movement of horses across the track and interference with other runners, and therefore no evidence whipping improves safety. This adds to evidence from jumps racing that .

5. …or fairer…

The gambling industry has an interest in ensuring races are run with integrity, lest punters take their dollars elsewhere. Whip use is arguably the most visible sign that jockeys are indeed trying their hardest.

But the revealed no difference between "whipping-free" and conventional races in terms of the number of incidents related to jockey behavior, such as careless riding or jockeys "dropping their hands" (indicative of not pushing the horse to run on).

The key to a fair race is not encouraging jockeys to use the whip, but rather ensuring all jockeys are subject to the same rules.

6. … or faster

The received wisdom is that whipping any horse makes it more likely to win. However, studies have shown increased whip use does not significantly affect , and the comparison study cited above between whipping-free and conventional races.

What's more, in "hands and heels" races, the jockey's center of mass is likely to remain directly above the horse's center of mass for more of the time, compared with when the jockeys are whipping the horses. So, the biomechanics of whip-free racing are arguably better for equine performance.

7. Whip rules are hard to police

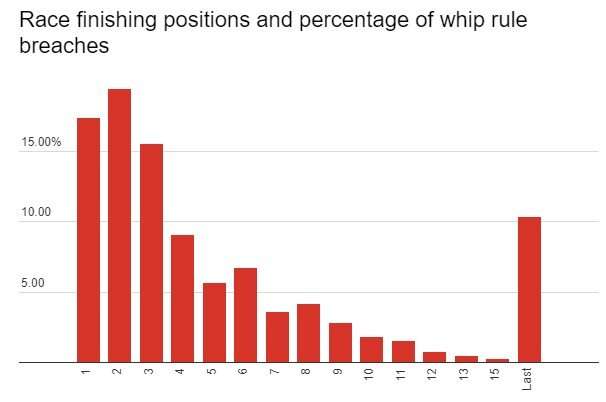

The most around whip use involve forehand strikes on more than five occasions before the 100-meter mark (44%), and the jockey's arm being raised above shoulder height (24%). of 15 races revealed at least 28 rule breaches, involving nine horses, that were not recorded in stewards' reports.

There are two reasons for this: the footage seen by racing stewards is filmed head-on, and is recorded at fewer frames per second than high-resolution video now provides. Head-on footage is preferred by stewards as it allows estimations of whip use on both sides of the horse, but it makes it harder to accurately police other aspects of whip use, such as the use of excessive force.

A revealed more breaches are recorded at metropolitan than country or provincial racecourses, and by riders of horses that finished first, second, or third rather than in other positions. That said, horses that finished last were also worryingly vulnerable to whip-rule breaches.

What's more, even is likely to cause significant pain, given the similarity of human and horse skin.

8. The public supports a ban on whipping

In a recent of more than 1,500 Australian adults, 75% thought horses should not be hit with a whip in the normal course of a race. The survey also found men were more than twice as likely as women to support whipping racehorses. Even among respondents who attended races or gambled on them at least once a week, 30% disagreed with whipping.

9. Whip-free racing still allows betting

While the ethics of promoting gambling is a different debate entirely, in Norway and the UK still allow people to bet. It may even be more attractive to sponsors seeking assurance their brand is only associated with ethical activities.

10. Whipping tired animals in the name of sport is hard to justify

Horses have evolved to run away from painful pressure on their hindquarters, given the most likely natural cause of such stimulation is contact from a predator. Repeatedly whipping tired horses in the closing stages of a race is likely to be distressing and cause suffering. The horse's loss of agency as it undergoes repeated treatment of this sort is thought to lead to the state of "," in which animals learn they can do nothing to end their distress.

Racing must reckon with two key questions: does whipping actually work as intended, and is it an ?

If the answer to both of those is "no," a third question arises: why are jockeys still doing it?

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons license. Read the .![]()