Building a detailed seafloor map to reveal the ocean's unknowns

Marine scientists often feel like they're . The global ocean covers about 71 percent of our planet and is central to life as it exists on Earth. But of the seafloor has been directly mapped so far.

equipped with sonars called are being used to measure the depth of the seafloor to better understand it. But the size of the job is enormous. A single to adequately map most of the seabed deeper than 200 meters, and it would take another 620 years to map the shallower areas.

We must . Today, marine surveying, or , is central to major international initiatives, including one that aims to see all of the ocean floor .

A more detailed and accurate global model of water depth would reveal the seafloor's shape, and the data can be used to . This will increase the , inform operations, , support various sectors of the and guide decisions on . But it could also come with .

Unknown sea

In 2007, as an undergraduate co-op student working at the Pacific Geoscience Center near Victoria, B.C., I helped map seabed habitats and hazards off the West Coast.

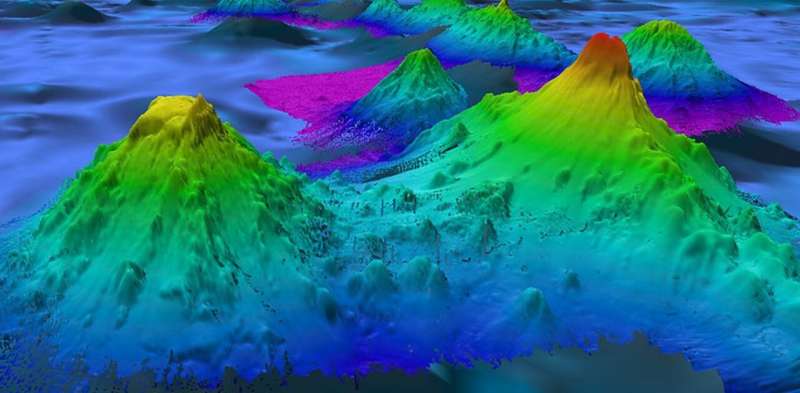

Looking at these digitally mapped areas of Canada's undersea terrain between northern Vancouver Island and the Alaskan border was like peering out the window of an airplane. I could see prominent canyons and imposing mountains hidden deep beneath the waves. On the relatively shallow lay the submerged remnants of coastal landforms like river banks, beaches and deltas. may have walked there when the .

We examined the depth of the seafloor, known as bathymetry, that had been collected by the with a mounted on the underbelly of a research ship. These sonar systems emit pings in a fan-shaped pattern and listen for returning seabed echoes. The depth of the sea is calculated by measuring the time between a ping and the return of its echo. But as sound beams spread through deeper water and "paint" more seabed terrain, the resolution of the map decreases.

The detailed bathymetry from multibeam sonar surveys off the reminded me of . But what intrigued me most were the gaps. There were vast areas, under both shallow and deep water, that lacked any high-resolution bathymetry. Mare incognitum—unknown sea.

There remain immense landscapes spread across most of our planet's solid surface that no human has ever seen or explored.

Mapping the gaps

Ocean mapping is now central to two major international initiatives, the and the . The latter aims to see all of the ocean floor mapped by 2030 through voluntary data contributions by governments, industry, researchers and others. Although to finish detailed nearshore surveys.

Multibeam bathymetry is much more detailed than the satellite of that provide much of the background imagery for services like . Satellite bathymetry has an average resolution of about —where one pixel represents an area eight kilometers by eight kilometers in size. This means that entire submarine mountains may not be captured.

Most of the elevation surface of Mars, which lacks an envelope of water, has been mapped with to a . That means we have a clearer picture of the terrain on that alien world than our own ocean floor. However, multibeam sonar can be made into a grid with a few meters resolution or better when collected from ship surveys in or from with robotic vehicles.

The Seabed 2030 bathymetry product will consist of grids that . Across the deepest regions of the ocean (six kilometers to 11 kilometers), survey efforts could be distilled to a single depth value for each 800 meter by 800 meter area. For seas shallower than 1.5 kilometers, the project would determine the depth of 100 meter by 100 meter units (100 meter grid resolution).

Before the 2017 launch of Seabed 2030, only of the ocean floor had been adequately mapped. In just five years, the compilation of detailed area has more than tripled to . Much of this rapid progress has been due to the public release of existing data.

Seabed 2030's objectives could be met sooner if , petroleum companies, and others are willing to share any of their previously unreleased bathymetric data.

The ocean frontier

Ocean and space exploration . are now using on extended missions. These robotic surveyors can be monitored and directed from mission control centers on land, or launched from crewed research vessels. reduces costs, safety concerns and carbon emissions.

Data from can be uploaded via to the cloud. Then that leverage artificial intelligence could free up ocean mappers onshore to spend more time solving scientific and applied problems.

Society can benefit greatly from an increase in the quantity and quality of seabed data. With an upgraded map of seabed shape and texture, we'll improve simulations of how water is steered by an irregular seabed, and how it slows due to bottom friction. This can help us make more accurate predictions about , , waves and . It will also help us understand how affects weather and climate.

As more detailed bathymetry is , we'll learn which seabed regions should be protected to . We'll also discover deposits of the for electric car batteries and mobile devices.

A flood of mapping data is revealing "planet ocean." it with greater wisdom than we have in the past?

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons license. Read the .![]()