Mini creatures with mighty voices know their audience and focus on a single frequency

In the cloud forests of South America, amid the constant cacophony of bird and insect noise, a deafening blare pierces through the background from time to time. Belonging to the loudest known bird, the white bellbird, Procnias albus, this sound would be painful to humans listening nearby and capable of causing .

, these vocalizations can reach peak levels of more than 120 decibels on the sound pressure level scale (dB SPL), which is equivalent to a . , presumably trading off being close enough to assess his quality as a mate without damaging her ears.

I study the to communicate. A great number of calls exist throughout the animal kingdom—and many are used to attract mates or defend territories. Evolution has favored those able to make sounds efficiently. The the energy in the call and the it is to the intended listener's optimal hearing range, the farther away a potential mate or rival will hear it.

Many large mammals, such as singing whales, roaring lions and rumbling elephants, that travel especially well through most habitats. Because of their petite physical size, small animals are not capable of making these far-reaching low-frequency sounds.

As a workaround, a number of small creatures have found ingenious ways to deliver their messages loudly, despite their size.

Ultrasonic calls

Human ears are most sensitive to the —about 4 kHz—a unit of measurement that is the physical metric for pitch. Anything above 20 kHz is considered ultrasonic—undetectable to human ears. But such sounds are not undetectable to all ears.

For example, the greater bulldog bat, Noctilio leporinus, can produce when hunting prey and maneuvering during flight. These calls can also get .

Many other small mammals, including other bats, and even some primates such as tiny tarsiers, produce . In part, these sounds can reach such volumes because their acoustic power is concentrated in a pure tone or single frequency.

Creating speakers

Insects are some of the smallest animals to produce loud sounds, chief among them the cicadas and the orthopterans, which include katydids, grasshoppers and crickets.

In North America, the robust conehead, Neoconocephalus robustus, a type of katydid, . These calls are produced to attract mates and, like many such calls, are competing against a clamor of comparable sounds from similar species.

Some insects go one step further, amplifying their sounds by building the functional equivalent of audio speakers. Some tree crickets chew holes in leaves, place their vibrating wings in the opening and to prevent the loss of sound energy around the edges of their wings.

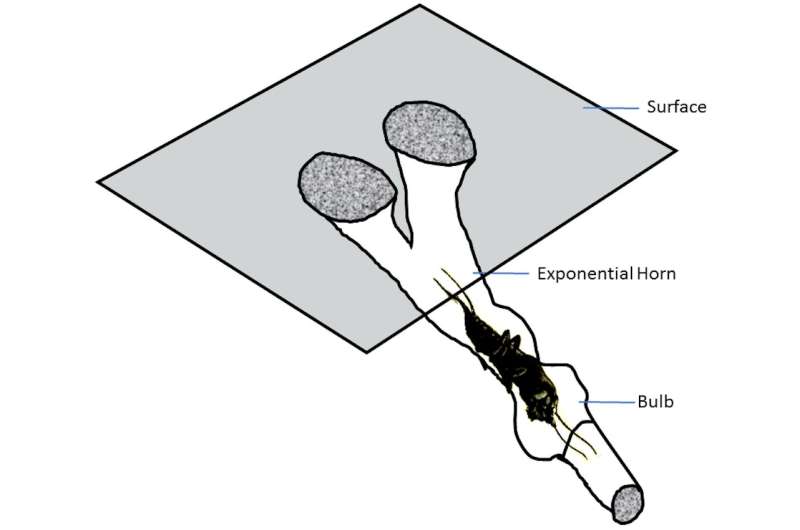

Mole crickets, Gryllotalpa vineae, go even further by , creating a cavity of vibrating air that amplifies the sound energy they produce. (0.8 kilometer).

Irksome invaders

The is a 1-to-2-inch (2-5-centimeter) frog called the coquÃ, Eleutherodactylus coqui, whose call is a combination of two pure tones—"ko" and "kee," from which it gets its name. At 114-120 dB SPL, the frog's calls are so loud they actually must , by increasing the air pressure inside their middle ear.

Unfortunately, in the past few decades humans have accidentally to a number of areas outside their native range, in particular the Hawaiian islands, and . Since coquà calls are within an octave of humans' best hearing—and they're nocturnal—many Hawaiians suffer .

So even if you're small, it's not impossible to make yourself heard. You just have to blast all your acoustic energy in a single frequency, and hit the sweet spot of your audience's hearing.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons license. Read the .![]()