The nuclear arms race's legacy: Toxic contamination, staggering cleanup costs and a culture of government secrecy

Christopher Nolan's film "" has focused new attention on the legacies of the —the World War II program to develop nuclear weapons. As the anniversaries of the on Aug. 6 and Aug. 9, 1945, approach, it's a timely moment to look further at dilemmas wrought by the creation of the atomic bomb.

The Manhattan Project spawned a trinity of interconnected legacies. It initiated a global arms race that threatens the survival of humanity and the planet as we know it. It also led to widespread public health and environmental damage from nuclear weapons production and testing. And it generated a culture of governmental secrecy with troubling political consequences.

examining communication in science, technology, energy and environmental contexts, I've studied these . From 2000 to 2005, I also served on a that provides input to federal and state officials on a massive environmental cleanup program at the in Washington state that continues today.

Hanford is less well known than Los Alamos, New Mexico, where scientists designed the first atomic weapons, but it was also crucial to the Manhattan Project. There, an enormous, secret industrial facility produced the plutonium fuel for the on July 16, 1945, and the bomb that incinerated Nagasaki a few weeks later. (The Hiroshima bomb was fueled by uranium produced in at another of the principal Manhattan Project sites.)

Later, workers at Hanford used in the U.S. nuclear arsenal throughout the Cold War. In the process, Hanford became one of the most contaminated places on Earth. Total cleanup costs are projected to reach , and the job won't be completed for decades, if ever.

Victims of nuclear tests

Nuclear weapons production and testing have harmed public health and the environment in multiple ways. For example, a new study released in preprint form in July 2023 while awaiting scientific peer review finds that fallout from the Trinity nuclear test .

Dozens of families who lived near the site—many of them Hispanic or Indigenous—were unknowingly exposed to radioactive contamination. So far, they in the federal program to " who developed radiation-linked illnesses after exposure to later atmospheric nuclear tests.

On July 27, 2023, however, the U.S. Senate voted to extend the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act and in New Mexico. A companion bill is under consideration in the House of Representatives.

The , along with tests conducted underwater, took place in the Pacific islands. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union and other nations conducted their own testing programs. , nuclear-armed nations exploded 528 weapons above ground or underwater, and an additional 1,528 underground.

Estimating from these tests is notoriously difficult. So is accounting for that were displaced by these experiments.

Polluted soil and water

Nuclear weapons production has also exposed many people, communities and ecosystems to radiological and toxic chemical pollution. Here, Hanford offers troubling lessons.

Starting in 1944, workers at the remote site in eastern Washington state irradiated uranium fuel in reactors and then dissolved it in acid to extract its plutonium content. Hanford's nine reactors, located along the Columbia River to provide a source of cooling water, discharged water into the river through .

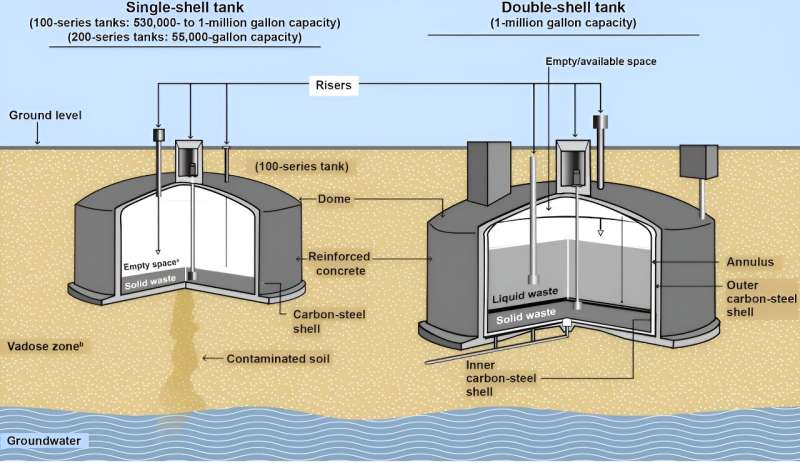

Extracting plutonium from the irradiated fuel, an activity called reprocessing, generated 56 million gallons of liquid waste laced with radioactive and chemical poisons. The wastes were stored in designed to last 25 years, based on an assumption that a disposal solution would be developed later.

Seventy-eight years after the first tank was built, that solution remains elusive. A project to vitrify, or for permanent disposal, has been , and repeatedly threatened with cancelation.

Now, officials are considering mixing some radioactive sludges and shipping them elsewhere for disposal—or perhaps leaving them in the tanks. Critics regard those proposals as . Meanwhile, an of liquid waste have leaked from some tanks into the ground, threatening the Columbia River, a backbone of the Pacific Northwest's economy and ecology.

Radioactive trash still litters parts of Hanford. Irradiated bodies of laboratory animals were . The site houses radioactive debris ranging from medical waste to and that partially melted down at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania in 1979. Advocates for a full Hanford cleanup warn that without such a commitment, the site will become a "," a place abandoned in the name of national security.

A culture of secrecy

As the movie "Oppenheimer" shows, government secrecy has shrouded nuclear weapons activities from their inception. Clearly, the science and technology of those weapons have dangerous potential and require careful safeguarding. But , the principle of secrecy quickly expanded more broadly. Here again, Hanford provides an example.

Hanford's reactor fuel was sometimes reprocessed before its most-highly radioactive isotopes had time to decay. In the 1940s and 1950s, managers , contaminating farmlands and pastures downwind. Some releases supported an . By tracking deliberate emissions from Hanford, scientists learned better how to spot and evaluate Soviet nuclear tests.

In the mid-1980s, local residents grew suspicious about an apparent excess of illnesses and deaths in their community. Initially, strict secrecy—reinforced by the region's economic dependence on the Hanford site—made it hard for concerned citizens to get information.

Once the curtain of secrecy was under pressure from area residents and journalists, public outrage prompted that engendered fierce controversy. By the close of the decade, more than 3,500 "downwinders" had filed lawsuits related to illnesses they attributed to Hanford. A judge finally in 2016 after awarding limited compensation to a handful of plaintiffs, leaving a bitter legacy of legal disputes and personal anguish.

Cautionary legacies

Currently active atomic weapons facilities also have seen their share of nuclear and toxic chemical contamination. Among them, —home to Oppenheimer's original compound, and now a site for both military and civilian research—has contended with , related to the toxic metal beryllium, and gaps in emergency planning and .

As Nolan's film recounts, J. Robert Oppenheimer and many other Manhattan Project scientists had about how their work might create unprecedented dangers. Looking at the legacies of the Trinity test, I wonder whether any of them imagined the scale and scope of those outcomes.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons license. Read the .![]()