Not religious, not voting? The 'nones' are a powerful force in politics, but are not yet a coalition

Nearly 30% of Americans say they . Today the so-called "nones" represent —and they are making their voices heard. on behalf of , agnostics, and other nonreligious people.

As more people leave religious institutions, or never join them in the first place, it's easy to assume this demographic will command more influence. But as a sociologist , I wanted to know whether there was evidence that this religious change could actually make a strong political impact.

There are reasons to be skeptical of unaffiliated Americans' power at the ballot box. Religious institutions have long been key for mobilizing voters, both and . Religiously unaffiliated people , and younger people . What's more, from show the religiously unaffiliated may be a smaller percentage of voters than of the general population.

Most importantly, it's hard to put the "unaffiliated" in a box. Only a third of them . While there is a smaller core of , they tend to hold different views from of people who are religiously unaffiliated, such as being more concerned about the separation of church and state.

By combining all unaffiliated people as "the nones," researchers and political analysts risk missing key details about this large and diverse constituency.

Crunching the numbers

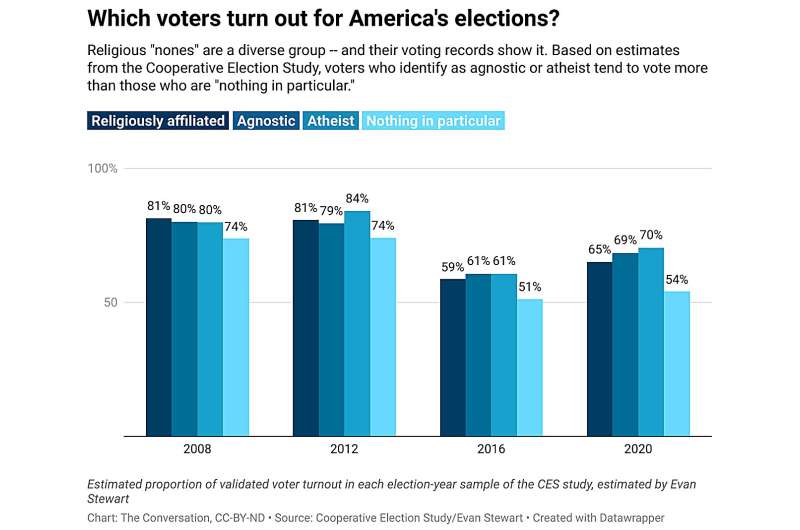

In order to learn more about which parts of religious unaffiliated populations turn out to vote, I used data from the , or CES, for presidential elections in 2008, 2012, 2016 and 2020. The CES collects large surveys and then matches individual respondents in those surveys to validated voter turnout records.

These surveys were different from exit polls in some key ways. For example, according to these survey samples, overall validated voter turnout looked higher in many groups, not just the unaffiliated, than exit polls suggested. But because each survey sample had more than 100,000 respondents and detailed questions about religious affiliation, they allowed me to find some important differences between smaller groups within the unaffiliated.

My findings, , were that the unaffiliated are divided in their voter turnout: Some unaffiliated groups are more likely to vote than religiously affiliated respondents, and some are less likely.

People who identified as atheists and agnostics were more likely to vote than religiously affiliated respondents, especially in more recent elections. For example, after controlling for key demographic predictors of voting—like age, education and income— that atheists and agnostics were each about 30% more likely to have a validated record of voting in the 2020 election than religiously affiliated respondents.

With those same controls, people who identified their religion as simply "nothing in particular," , were actually less likely to turn out in all four elections. In the 2020 election sample, for example, that about seven in 10 agnostics and atheists had a validated voter turnout record, versus only about half of the "nothing in particulars."

Together, these groups' voting behaviors tend to cancel each other out. Once I controlled for other predictors of voting like age and education, "the nones" as a whole were equally likely to have a turnout record as religiously affiliated respondents.

2024 and beyond

Concern about growing Christian nationalism, which advocates for fusing national identity and political power with Christian beliefs, has put a spotlight on religion's role in .

Yet religion does not line up neatly with one party. The , and there are many Republican voters for whom religion is not important.

If the percentage of people without a religious affiliation continues to rise, both Republicans and Democrats will have to think more creatively and intentionally about how to appeal to these voters. My research shows that neither party can take the unaffiliated for granted nor treat them as a single, unified group. Instead, politicians and analysts will need to think more specifically about what motivates people to vote, and particularly what policies encourage voting among young adults.

For example, some activist groups talk about "": someone who is increasingly motivated to vote by concern about separation of church and state. I did find evidence that the average atheist or agnostic is about 30% more likely to turn out than the average religiously affiliated voter, lending some support to the secular values voter story. At the same time, that description does not fit ."

Instead of focusing on America's declining religious affiliation, it may be more helpful to focus on the country's , especially because many unaffiliated people still report having religious and spiritual beliefs and practices. Faith communities have historically been important sites for political organizing. Today, though, motivating and empowering voters might mean looking across a broader set of community institutions to find them.

Rethinking assumptions

There is good news in these findings for everyone, regardless of their political leanings. that leaving religion was part of a larger trend in declining civic engagement, like voting and volunteering, but that may not be the case.

, it was actually unaffiliated respondents who reported still attending religious services who were least likely to vote. Their turnout rates were lower than both frequently attending religious affiliates and unaffiliated people who never attended.

This finding matches up with previous research on religion, spirituality and other kinds of civic engagement. Sociologists and , for example, found among religiously unaffiliated respondents. In a previous study, sociologist and I found that spiritual practices like meditation and yoga were just as strongly associated with political behavior as religious practices like church attendance. Across these studies, it looks like disengagement from formal religion is not necessarily linked to political disengagement.

As the religious landscape changes, new potential voters may be ready to engage—if political leadership can enact policies that help them turn out, and inspire them to turn out, too.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons license. Read the .![]()