Study reveals how corals control their algae population

A , published by KAUST researchers in Nature Communications, shows that corals, jellyfish, and other symbiotic cnidarians control their symbiotic algae by limiting the amount of nitrogen available for proliferation.

The findings disrupt traditional views of cooperative symbiosis in corals and have important implications for major coral reef restoration efforts such as the KAUST Reefscape Restoration Initiative, which covers more than 100 hectares of the Red Sea.

By tracking nutrient exchange using carbon and nitrogen isotopes, the study shows how three distinct cnidarian species, including corals, have independently evolved this common mechanism for symbiosis with marine algae (dinoflagellates).

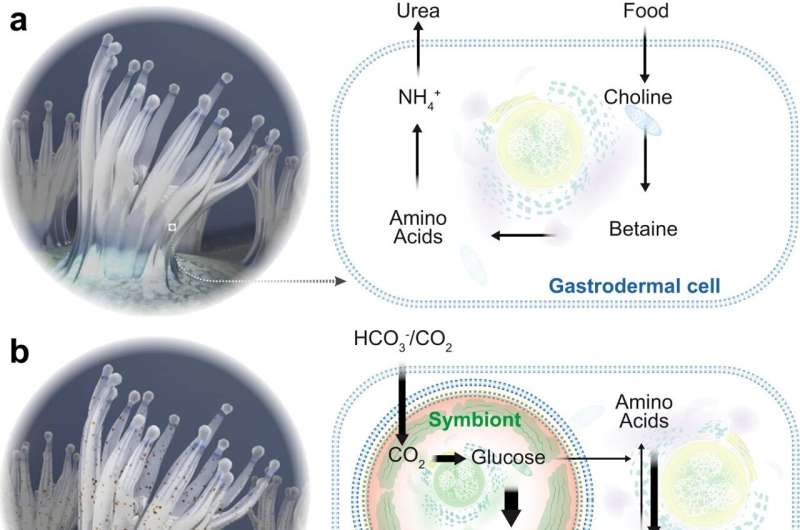

The researchers investigated how sea anemones, jellyfish, and corals control their algal symbiont population by tracing carbon and nitrogen isotopes in glucose and ammonium, respectively. The researchers found that more ammonium promotes the algae population size because of the greater access to nitrogen, while more glucose reduces the population size since glucose promotes the ability of the host to assimilate more of its nitrogen waste.

"The hosts use the sugar provided by the symbionts through their photosynthetic processes to assimilate their own nitrogen waste into amino acids. This limits the amount of nitrogen available to the symbionts. Essentially, the host gives the symbiont just enough nitrogen to function and keep photosynthesizing, but not enough to use the sugar they produce to proliferate," explained KAUST Prof. Manuel Aranda, who managed the study.

The symbiosis between algae and cnidarians (including sea anemones, jellyfish, and corals) is critical for cnidarians to thrive in the nutrient-poor waters of the tropics. The symbiosis is so strong that the algal symbionts live inside the hosts' cells. However, for both creatures to grow healthily, the symbiont's population size must be strictly controlled.

Lead researcher of the study, Dr. Guoxin Cui, said, "Climate change will significantly disrupt the carbon-nitrogen balance in cnidarian-algae symbiosis, a disturbance that triggers symbiosis breakdown, commonly referred to as coral bleaching, which in turn leads to the global decline of coral reefs."

"Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying these symbioses, particularly the carbon-nitrogen negative feedback loop, opens new avenues for enhancing reef restoration strategies, such as selecting symbiotic partners that are better suited to forming colonies with greater resilience to environmental changes."

This knowledge will likely inspire further investigations into the regulatory mechanisms governing these relationships and inform policy-making to develop effective restoration strategies.

"By confirming that the same mechanism operates in such distinct species, we demonstrated that a common mechanism allowed these symbioses to evolve repeatedly. This is another example of how clever and yet simple nature can be and provides us with a framework to better understand corals and their sensitivity to climate change." said Aranda.

More information: Guoxin Cui et al, A carbon-nitrogen negative feedback loop underlies the repeated evolution of cnidarian–Symbiodiniaceae symbioses, Nature Communications (2023).

Journal information: Nature Communications