Two mathematicians explain how building bridges within the discipline helped prove Fermat's last theorem

On June 23, 1993, the mathematician gave the last of three lectures detailing to , a problem that had remained unsolved for three and a half centuries. Wiles' announcement caused a sensation, both within the and .

Beyond providing a satisfying resolution to a long-standing problem, Wiles' work marks an important moment in the establishment of a bridge between two important, but seemingly very different, areas of mathematics.

History demonstrates that many of the greatest breakthroughs in math involve making connections between seemingly disparate branches of the subject. These bridges allow mathematicians, like , to transport problems from one branch to another and gain access to new tools, techniques and insights.

What is Fermat's last theorem?

Fermat's last theorem is similar to the , which states that the sides of any right triangle give a solution to the equation x2 + y2 = z2 .

Every differently sized triangle gives a different solution, and in fact there are where all three of x, y and z are whole numbers—the smallest example is x=3, y=4 and z=5.

Fermat's last theorem is about what happens if the exponent changes to something greater than 2. Are there whole-number solutions to x3 + y3 = z3 ? What if the exponent is 10, or 50, or 30 million? Or, most generally, what about any positive number bigger than 2?

Around the year 1637, claimed that the answer was no, there are no three positive whole numbers that are a solution to xn + yn = zn for any n bigger than 2. The French mathematician scribbled this claim of his copy of a , declaring that he had a marvelous proof that the margin was "too narrow to contain."

Fermat's purported proof was never found, and his "last theorem" from the margins, by his son, went on to plague mathematicians for centuries.

Searching for a solution

For the next 356 years, no one could find Fermat's missing proof, but no one could prove him wrong either—not even . The theorem quickly gained a reputation for being incredibly difficult or even impossible to prove, with put forward. The theorem even earned a spot in the Guinness World Records as the "."

That is not to say that there was no progress. had proved it for n=3 and n=4. Many other mathematicians, including the trailblazer , contributed proofs for individual values of n, inspired by Fermat's methods.

But knowing Fermat's last theorem is true for certain numbers isn't enough for mathematicians—we need to know it's true for infinitely many of them. Mathematicians wanted a proof that would work for all numbers bigger than 2 at once, but for centuries it seemed as though no such proof could be found.

However, toward the end of the 20th century, a growing body of work suggested Fermat's last theorem should be true. At the heart of this work was something called the modularity conjecture, also known as the .

A bridge between two worlds

The modularity conjecture proposed a connection between two seemingly unrelated mathematical objects: and .

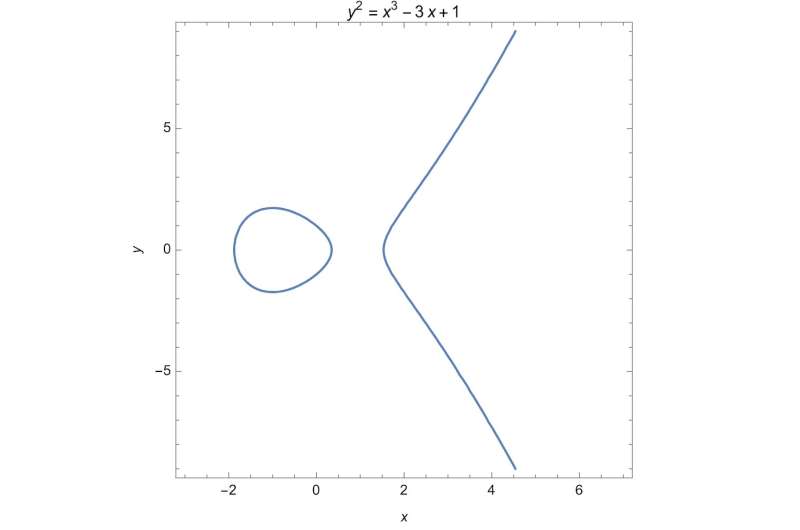

Elliptic curves are neither ellipses nor curves. They are doughnut-shaped spaces of solutions to cubic equations, like y2 = x3—3x + 1.

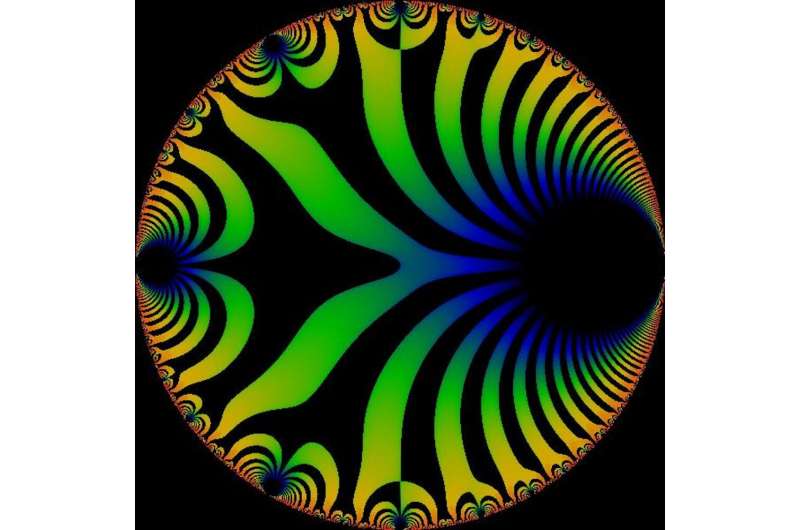

A modular form is a kind of function which takes in certain complex numbers—numbers with two parts: a real part and an imaginary part—and outputs another complex number. What makes these functions special is that they are , meaning there are lots of conditions on what they can look like.

There is no reason to expect that those two concepts are related, but that is .

Finally, a proof

The modularity conjecture doesn't appear to say anything about equations like xn + yn = zn . But work by mathematicians in the 1980s showed a link between these new ideas and Fermat's old theorem.

First, in 1985, that if Fermat was wrong and there could be a solution to xn + yn = zn for some n bigger than 2, that solution would produce a peculiar elliptic curve. Then in 1986 that such a curve could not exist in a universe where the modularity conjecture was also true.

Their work implied that if mathematicians could prove the modularity conjecture, then Fermat's last theorem had to be true. For many mathematicians, including Andrew Wiles, working on the modularity conjecture became a path to proving Fermat's last theorem.

Wiles worked for seven years, , trying to prove this difficult conjecture. By 1993, he was close to having a proof of a special case of the modularity conjecture—which was all he needed to prove Fermat's last theorem.

He presented his work in a at the Isaac Newton Institute in June 1993. Though subsequent peer review found a gap in Wiles' proof, Wiles and his former student worked for another year to and cement Fermat's last theorem as a mathematical truth.

Lasting consequences

The impacts of Fermat's last theorem and its solution continue to reverberate through the world of mathematics. In 2001, a group of researchers, including Taylor, gave a of in a that were inspired by Wiles' work. This completed bridge between elliptic curves and modular forms has been—and will continue to be—foundational to understanding mathematics, even beyond Fermat's last theorem.

Wiles' work is cited as beginning "" and is central to important pieces of modern math, including a widely used and a huge research effort known as the that aims to build a bridge between two fundamental areas of mathematics: algebraic number theory and harmonic analysis.

Although Wiles worked mostly in isolation, he ultimately needed help from his peers to identify and fill in the gap in his original proof. Increasingly, mathematics today is a , as witnessed by what it took to finish proving the modularity conjecture. The problems are large and complex and often require a variety of expertise.

So, finally, did Fermat really have a proof of his last theorem, as he claimed? Knowing what mathematicians know now, many of us today don't believe he did. Although Fermat was brilliant, he was sometimes wrong. Mathematicians can accept that he believed he had a proof, but it's unlikely that his proof would stand up to modern scrutiny.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons license. Read the .![]()