Your genetic code has lots of 'words' for the same thing—information theory may help explain the redundancies

Nearly all life, from bacteria to humans, uses the same . This code acts as a dictionary, translating genes into the amino acids used to build proteins. The indicates a common ancestry among all living organisms and the essential role this code plays in the structure, function and regulation of biological cells.

Understanding how the genetic code works is the foundation of and . But there are still many unsolved mysteries, such as why the code is important for various biological processes such as protein folding.

As a , I apply information theory—the mathematics of how information is stored and communicated—to study some of these intriguing questions. Just as computers need strings of binary code to function, also rely on bits of information.

In my , I propose that may provide a potential explanation for a long-standing mystery about a certain redundancy in how amino acids are encoded.

Different words for the same thing

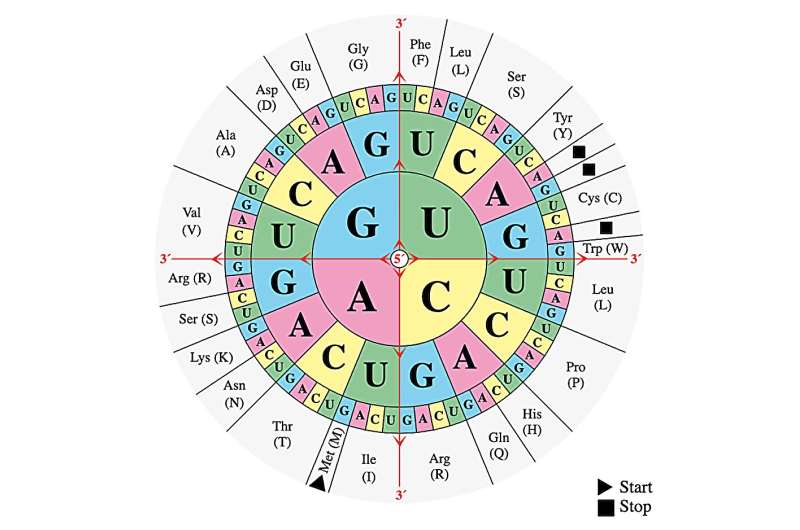

The genetic codebook is made of "words" composed of four letters: A, C, G and U. Each of these letters stands for a different chemical building block : adenine, cytosine, guanine and uracil. A molecular machine reads the codebook to translate genes into proteins.

Ribosomes read three-letter words , and there are 64 different possible combinations of the four letters that make different codons. In this list of 64 words, 61 , and three signal the ribosome to stop protein synthesis in the cell. For example, "AUG" codes for the amino acid methionine and also indicates the start of a protein.

But just as in any other language, there are synonyms—different codons can encode the same amino acid. In fact, since there are only 20 amino acids but 61 different words to encode them, there is quite a lot of overlap. An amino acid can have anywhere from one to six different codons that encode it. There are only two amino acids that have , methionine and trytophan. This redundancy helps ribosomes perform their tasks correctly even when there's a .

Engineering nature's guidelines

Why certain amino acids have more synonyms than others is a mystery that has puzzled scientists for decades. Is there a pattern to this variability, or is it random? To answer this question, scientists study the rules that govern nature's decision-making.

If a human engineer designed the genetic code, they would want to make sure that each amino acid had a similar degree of redundancy to protect against errors and to promote uniformity. The mapping of the 61 codes onto the the 20 amino acids would be roughly equal, with each amino acid assigned three codons.

But nature has different priorities. Evolutionary models of natural systems like bacteria demonstrate that nature is always . Not only does the final form of a protein need to be optimal, but so do its intermediate forms. Optimization ensures that natural systems can adapt to different environments.

Scientists understand some of the guidelines that nature follows when engineering the genetic code. For instance, the within and surrounding the genetic code can affect its function, as well as the involved in creating proteins.

Information theory and genetics

that there may be two other significant factors that natural systems consider: the information-theoretic nature of the genetic code and the principle of maximum entropy.

Paralleling how the computer processes data consisting of 0s and 1s, life processes the genetic code based on data consisting of the four letters A, C, G and U. Mathematically, however, the most energy-efficient way to represent data isn't binary (or base 2)—using 0s and 1s, as computers do—. Short for Euler's number, e is an irrational number—meaning that there's no way to write down its exact value using fractions or decimals (although it's approximately 2.718).

Nature's affinity for optimization using this irrational number is responsible for the infinitely repeating fractals seen in , . , information optimization using e also has applications in and .

Another principle operating in the natural world is that of . Entropy is a measure of disorder in a system, and the maximum entropy principle states that systems evolve to states of greater disorder. This principle allows researchers to from limited data and has been used to explain how .

In the context of codon groupings, the maximum entropy principle implies that nature is scrambling data as much as possible—meaning the function that describes the distribution of codon groupings should be mathematically difficult to undo. Studying how to maximize the mathematical complexity of this function underlying the codon groupings.

I believe these two principles may the distribution of the codon groups in the genetic code and point to the usefulness of mathematics in analyzing natural systems. Although there are many biological mysteries that scientists have yet to solve, information theory can be a powerful tool to help crack the genetic code.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons license. Read the .![]()