Who gets to decide what counts as 'disorder'?

, I viewed the responses to protests on U.S. campuses as about more than threats to academic freedom and freedom of speech.

They are also threats to the fundamental rights of .

The protesters' tactics, particularly their use of tents in encampments, have brought debates around definitions of public order and disorder to the fore.

Over the past couple of months, students in universities across the country, , have occupied courtyards, classrooms and libraries in solidarity with Palestinians. Students in Canada, Brazil and France have also joined in, setting up encampments to demand changes in their governments' policies toward Israel due to its war in the Gaza Strip.

Most encampments and buildings have been cleared —often by the police, sometimes with the use of . These police responses can have ripple effects in communities far beyond the university walls.

After studying the ways in which , I've started to view calls for public order with suspicion. When those in power frame dissent and poverty as disorder, more than freedom of expression is at stake.

Public order versus the 'right to the city'

As the populations of cities swelled during the 19th and 20th centuries, some residents started decrying the "disorder" of urban spaces.

Whether it was due to , informal markets or political protests, calls to tame the unruly city grew louder. Everything and everybody seen as undesirable, inadequate or a nuisance could be targeted.

Legislation like Virginia's —a concept that remains in the country's regulatory framework through state and local loitering laws. These statutes .

Other laws that have since been overturned—, public bathing laws —might sound ridiculous today, but they show how notions of what counts as disorder can change over time.

Laws that police what people can and can't do in public often conflict with what French philosopher called the "right to the city."

Laid out in his 1968 book "Le Droit à la Ville," it speaks to the right of all residents to shape and govern urban life. , the right to the city was seen as so important that it was included in the , which was signed at the United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development in 2016.

The issue today is that city residents with the least amount of power—the poor, the young, immigrants, people of color—have little say in how cities are governed. And public order laws tend to target them.

refer to the acts that disrupt the running of society. The U.S. has around .

Although public order is an important element of modern city life, it's also been used as a mechanism to and control—especially of the most vulnerable communities. Historically, public order has served to organize urban spaces, but also .

Last year, for example, the U.K. passed its , which gave the government the ability to break up protests deemed too noisy or unruly.

Clearing the camps

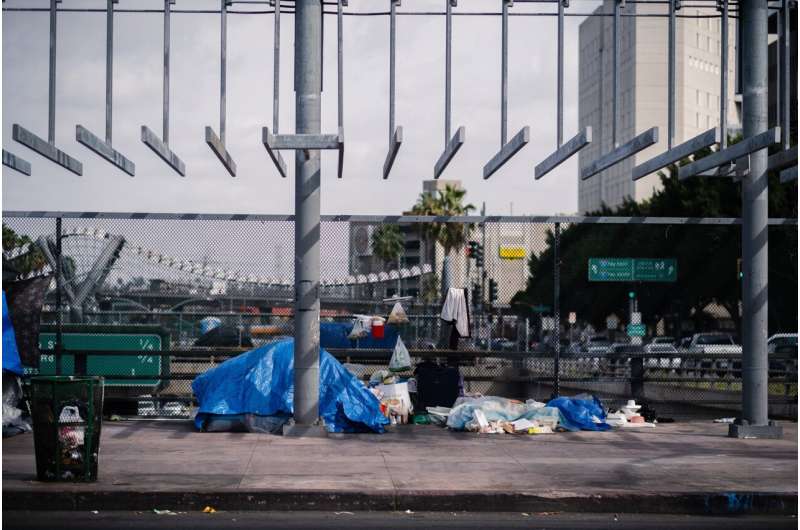

·¡²Ô³¦²¹³¾±è³¾±ð²Ô³Ù²õ——have been in the spotlight not only due to student protesters. Homeless communities also set up clusters of tents as makeshift shelters in public spaces. These have drawn the attention of city residents and policymakers, some of whom see them as unsightly symbols of disorder.

In cities where shelters are scarce or nonexistent and proper policies to tackle poverty and homelessness fall short, sleeping in tents and cars, on public transit or under bridges—all forms of ""—have become improvised responses .

The crackdown on rough sleeping can be both proactive and reactive. The implementation of spikes on ledges or bars on benches to prevent people from lying down—what's called hostile architecture—is a defensive approach. The clearing of encampments, meanwhile, might happen in response to complaints and outcry.

Regardless of the approach, you'll often as justifications.

Taming the city

Debates over order, disorder and the right to the city don't just involve whether people experiencing homelessness can sleep in public spaces. They also include alternative economies.

Can ? What about selling their wares?

Both groups .

When city leaders want to showcase their city, order becomes an even bigger priority.

For instance, in preparation , the then-mayor of Rio de Janeiro, Eduardo Paes, decided to create a Department of Public Order.

Through heavy policing, Paes tried to make the city look more orderly and safe for an international audience.

The reality meant brutal crackdowns in Rio's favelas, the city's informal settlements of improvised homes. The authorities . In other areas, they cleared the roads of street vendors and homeless people, while .

AI in the name of order

When new technologies enter the picture, public order is translated—and enforced—by big data. Some technocrats even envision .

In March 2024, news emerged that San Jose, California, was planning to use an artificial intelligence detection tool trained to identify "" in vehicles and encampments.

By targeting primarily people experiencing homelessness , these kinds of are worrisome trends. To me, they're representative of —the idea that all problems can be solved with technology.

Other controversial tools, such as and , have been met with backlash because of their potential to discriminate, encroach on privacy and profile people.

Facial recognition systems have triggered a series of , mostly affecting people of color. in some cities.

The indiscriminate deployment of AI in cities in technology and governments, and it's easy to see how deploying big data under the guise of enforcing public order can backfire, limiting freedom of expression and assembly while harming people living on the margins of society.

In "," explains how cities can provide something for everybody—that they are wellsprings of spontaneity, creativity and connection.

To me, surveillance, control and repression are at odds with these aims.

Order is ultimately an illusion. The right to the city means living with unpredictability, whether it's in the form of a student protest, a block party or a busker.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons license. Read the .![]()